What Are Bacterial Skin Infections?

Bacterial skin infections happen when bacteria sneak into your skin through a cut, scrape, insect bite, or even a tiny crack from dry skin or eczema. The two most common types you’ll see in clinics and emergency rooms are impetigo and cellulitis. They look different, act differently, and need totally different treatments. Getting the diagnosis right matters-mistake one for the other, and you could end up with a serious complication.

Impetigo: The Contagious Sores You See in Kids

Impetigo is the classic "school sore." It’s most common in children between 2 and 5 years old, but adults can get it too-especially if they’ve had skin injuries or live in crowded conditions. It’s not dangerous, but it spreads fast. One child with impetigo can trigger an outbreak in a daycare or classroom within days.

The most common form, nonbullous impetigo, starts as a tiny red bump or blister, usually around the nose or mouth. Within a day or two, it breaks open, oozes, and forms that unmistakable honey-colored crust. It’s not usually painful, but it itches. Bullous impetigo, which affects babies under 2, shows up as larger, fluid-filled blisters that burst and leave behind a ring-like border. About 5% of cases turn into ecthyma-deeper sores that scar.

Here’s what changed: for decades, doctors thought Group A Strep caused most impetigo. Now, we know better. Over 90% of cases are caused by Staphylococcus aureus, often mixed with strep. And here’s the kicker: nearly all of these staph strains make an enzyme called penicillinase, which breaks down penicillin. That means penicillin? Useless in about two-thirds of cases.

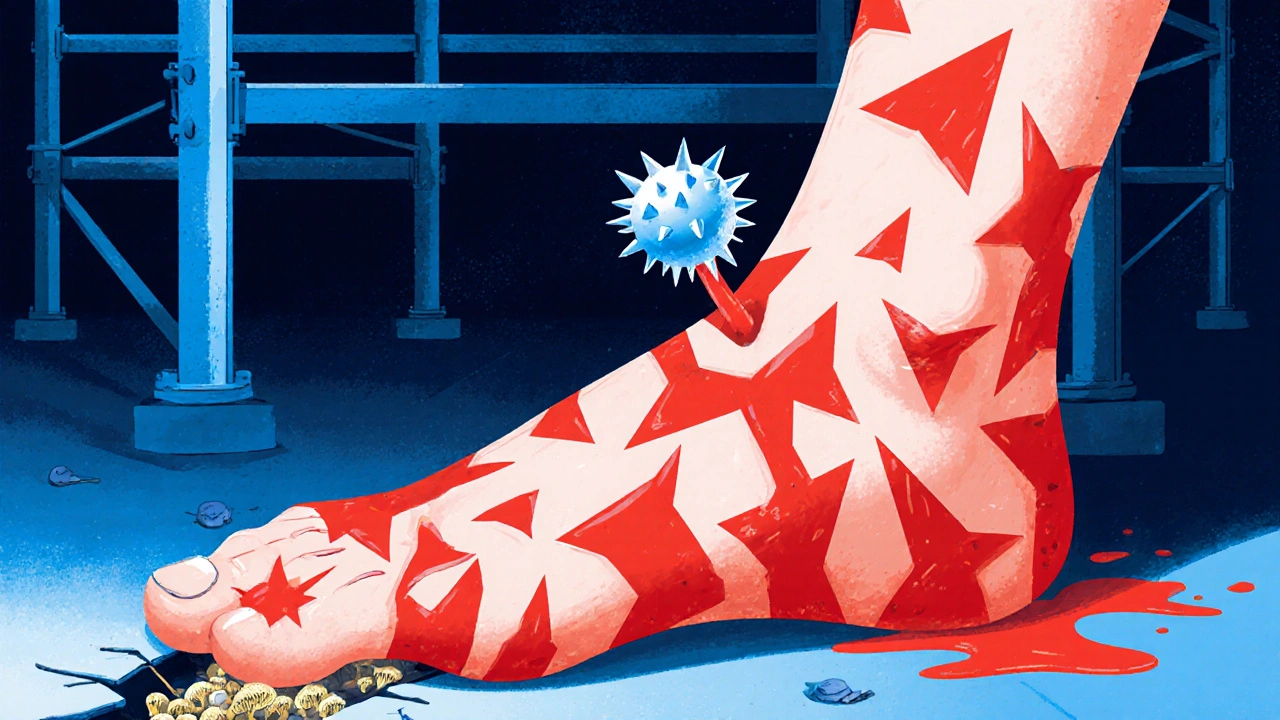

Cellulitis: When the Infection Goes Deep

Cellulitis is a whole different beast. It doesn’t sit on the surface. It burrows into the deeper layers of skin and fat, causing redness, swelling, warmth, and pain that spreads without clear edges. It’s most common on the lower legs in adults, especially in people over 65. About 65% of cases start after a small injury-a scrape, a bug bite, or a fissure from athlete’s foot.

Unlike impetigo, cellulitis isn’t contagious. You can’t catch it from touching someone’s skin. It comes from bacteria already on your body-usually Streptococcus pyogenes (strep) or Staphylococcus aureus-that got inside through a break. In fact, strep causes 60-80% of cellulitis cases, while staph makes up the rest.

Signs you’re in trouble: the red area grows more than 2 cm a day, you develop a fever over 101°F, or you feel generally sick. If the skin turns purple, blisters, or feels numb, it could be necrotizing fasciitis-a rare but deadly flesh-eating infection. That’s an emergency. Call 911.

Antibiotics: What Works, What Doesn’t

Treatment for impetigo and cellulitis isn’t interchangeable. You can’t use a cream for one and expect it to fix the other.

For mild, localized impetigo, topical mupirocin (Bactroban) is the gold standard. Apply it three times a day for five days after gently washing off the crusts with warm soapy water. Studies show a 92% cure rate. If the infection is widespread, bullous, or doesn’t improve, you need oral antibiotics like cephalexin or dicloxacillin.

For cellulitis, topical treatments won’t cut it. You need systemic antibiotics. Mild cases? Oral cephalexin (500 mg four times a day) or dicloxacillin for 5 to 14 days. But if you’re sick, have a fever, or the infection is spreading fast, you’ll likely need an IV antibiotic like cefazolin in the hospital.

Here’s the new reality: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is now behind half of community skin infections in the U.S. That means traditional antibiotics like cephalexin may fail. For suspected MRSA, guidelines now recommend doxycycline or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole as first-line oral options-with cure rates of 85-90%.

When to Worry: Complications and Red Flags

Impetigo rarely leads to big problems. But about 1-5% of cases caused by strep can trigger post-streptococcal acute glomerulonephritis-a kidney condition that shows up weeks later with dark urine, swelling, and high blood pressure. It’s rare, but it’s why doctors still test for strep in some cases.

Cellulitis? The stakes are higher. About 5-9% of cases lead to bacteremia (bacteria in the blood). In 0.3% of cases, it turns into necrotizing fasciitis. And 2-4% of hospitalized patients develop sepsis. People with diabetes, obesity, or poor circulation are at much higher risk. Diabetics are over three times more likely to get cellulitis.

And then there’s staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS)-a toxin-driven condition that mostly hits babies and toddlers. The skin turns red, blisters, and peels off like a burn. It looks terrifying, and yes, it can be fatal. If your child has a high fever and skin that looks scalded or is peeling, call emergency services immediately.

Diagnosis: No Lab Needed (Usually)

Most of the time, doctors diagnose impetigo and cellulitis by looking. No blood tests. No cultures. The appearance is so classic that testing isn’t needed unless the infection isn’t improving or there’s an outbreak.

But here’s what doctors rule out: for cellulitis, they check for deep vein thrombosis, gout, or stasis dermatitis-conditions that can mimic it. For impetigo, they make sure it’s not chickenpox, insect bites, or fungal infections.

There’s new hope on the horizon. Researchers are developing rapid point-of-care tests that can identify the exact bacteria and its resistance profile in under 30 minutes. The NIH is funding this work because it could cut down on useless antibiotics by 40%.

Prevention: Simple Steps, Big Impact

Impetigo spreads through touch-sharing towels, toys, or even a handshake. During outbreaks, daily washing with antibacterial soap helps. Keep fingernails short. Don’t pick at scabs. Wash clothes and bedding in hot water.

For cellulitis, the key is protecting your skin. Treat athlete’s foot. Clean minor cuts with soap and water. Use antiseptic on scrapes. If you have diabetes, check your feet every day. Moisturize dry skin. Preventing a break is the best defense.

Season matters too. Impetigo peaks in summer-hot, humid weather helps bacteria thrive. Cellulitis spikes in winter, when people get more skin injuries from falls and dry, cracked skin.

What’s Changing in Treatment?

Antibiotic resistance isn’t just a hospital problem-it’s in your neighborhood. In many places, 45% of staph infections are MRSA. That’s why guidelines changed. We don’t start with penicillin anymore. We don’t even start with cephalexin if MRSA is likely.

New topical treatments like retapamulin (Altabax) are showing 94% effectiveness in kids with impetigo. It’s not yet first-line everywhere, but it’s gaining ground. And antimicrobial stewardship programs are now pushing doctors to avoid antibiotics for mild rashes that might be viral or fungal.

The American Academy of Dermatology’s 2025 plan aims to cut unnecessary skin infection prescriptions by 30%. That means better diagnostics, better education, and smarter choices.

When to See a Doctor

See a doctor if:

- A rash with honey-colored crusts doesn’t improve in 3 days

- Redness spreads quickly, especially if it’s warm and painful

- You have a fever over 101°F with skin infection

- Your child’s skin is peeling like a burn

- You have diabetes and notice any red, swollen area on your legs or feet

Don’t wait. A small skin infection can become life-threatening in hours if it turns into sepsis or necrotizing fasciitis.

Is impetigo contagious?

Yes, impetigo is highly contagious. It spreads through direct skin contact or by touching objects like towels, toys, or clothing that have been contaminated. Children in daycare or school are especially at risk. Once antibiotic treatment starts, they’re no longer contagious after 24 hours-so it’s safe to return to school or childcare after that point.

Can I treat impetigo with over-the-counter creams?

No. Over-the-counter antibiotic ointments like Neosporin won’t work for impetigo. The bacteria causing it are resistant to the antibiotics in those creams. You need a prescription topical like mupirocin or an oral antibiotic if it’s widespread. Using the wrong product delays healing and increases the chance of spreading it.

Why don’t doctors always do a culture for impetigo or cellulitis?

Because the appearance is so distinctive. In most cases, doctors can diagnose based on symptoms and location alone. Cultures are only ordered if the infection doesn’t respond to treatment, if there’s an outbreak, or if the patient is very young, elderly, or immunocompromised. Testing takes days, and treatment needs to start right away.

Can cellulitis come back after treatment?

Yes, especially if the underlying cause isn’t addressed. People with diabetes, poor circulation, or chronic swelling in the legs are at higher risk for recurrence. Treating athlete’s foot, keeping skin moisturized, and managing weight can reduce the chance of it coming back. Some patients need long-term low-dose antibiotics to prevent repeat episodes.

Are antibiotics always necessary for bacterial skin infections?

Not always. Some very mild impetigo cases may clear on their own with good hygiene, but doctors still recommend antibiotics to prevent spread and complications. For cellulitis, antibiotics are essential. Without them, the infection can spread to the bloodstream and become life-threatening. The goal isn’t to avoid antibiotics entirely-it’s to use the right one, at the right dose, for the right length of time.

How long does it take to recover from cellulitis?

Most people start feeling better within 48 to 72 hours of starting antibiotics. The redness and swelling may take several days to weeks to fully go down, even after the infection is gone. It’s important to finish the full course of antibiotics-even if you feel fine. Stopping early increases the risk of recurrence or antibiotic resistance.

13 Comments