If you’ve landed here, you’re probably trying to make sense of a rare condition that causes relentless acid, stubborn ulcers, and confusing test names. The promise in the title is simple: a clear, team-based plan that covers diagnosis, treatment, and life with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome-without sugarcoating what’s complex or pretending there’s a single path for everyone.

TL;DR

- ZES happens when a gastrin-secreting tumor (gastrinoma) drives massive acid production, leading to ulcers, reflux, and diarrhea. About 20-30% link to MEN1.

- Best care is team care: gastroenterology, endocrinology, surgery, nuclear medicine/radiology, oncology, pathology, genetics, dietetics, and nursing working together.

- Diagnosis hinges on fasting gastrin with gastric pH, a secretin stimulation test, upper endoscopy, and somatostatin-receptor imaging (e.g., 68Ga/64Cu DOTATATE PET/CT).

- Treatment splits into acid control (high-dose PPIs +/- somatostatin analogs) and tumor control (surgery if localized, plus options like PRRT, targeted therapy, or CAPTEM when needed).

- MEN1 changes the playbook: broader hormone checks, genetic counseling, and different surgery thresholds. Long-term follow-up is non-negotiable.

Understanding ZES and Why Team Care Matters

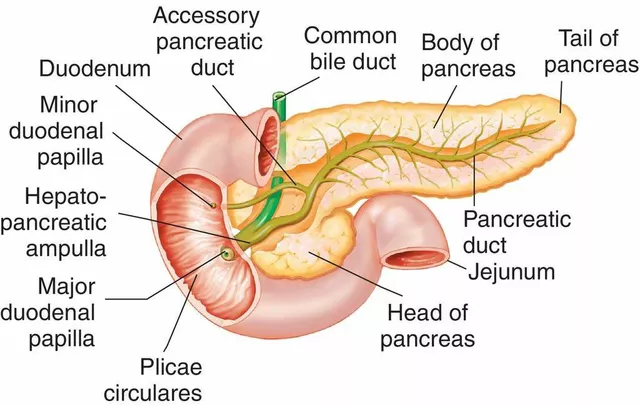

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES) is rare-think a handful of people per million. The core problem is a gastrinoma, usually in the duodenum or pancreas, that floods the body with gastrin. Gastrin tells the stomach to make acid, and in ZES it does that nonstop. That’s why patients get recurrent or multiple ulcers (often beyond the first part of the duodenum), reflux that laughs at standard doses, and watery diarrhea from acid drowning the small intestine.

Where are these tumors? About 60-70% sit in the duodenum, 20-30% in the pancreas, and a minority hide in lymph nodes. Many are small-duodenal gastrinomas can be tiny, so imaging needs to be sharp. Roughly one in four to one in three patients has multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1), an inherited condition that also involves the parathyroids and pituitary. That one fact changes workup, surgery decisions, and family screening.

Why a multidisciplinary team? Because ZES spans acid disease and neuroendocrine oncology:

- Gastroenterologist: nails the acid control, scopes for ulcers and thickened folds, coordinates testing.

- Endocrinologist: evaluates hormone syndromes and MEN1, orders genetic testing where appropriate.

- Surgeon (HPB): plans tumor removal when possible; thinks about duodenotomy for tiny lesions and node dissection.

- Nuclear medicine/radiology: handles 68Ga/64Cu DOTATATE PET/CT, EUS, and high‑resolution CT/MRI for staging and follow‑up.

- Medical oncologist: manages somatostatin analogs, PRRT, targeted drugs, and chemo when tumors spread.

- Pathologist: confirms neuroendocrine tumor, Ki‑67 grade, margins, and receptor expression.

- Genetic counselor: guides testing and family implications if MEN1 is suspected.

- Dietitian and pharmacist: fine‑tune meds, watch for deficiencies, and tailor eating plans when diarrhea or PPIs complicate life.

When should you suspect ZES?

- Refractory peptic ulcers or reflux on full‑dose PPIs.

- Multiple ulcers or ulcers beyond the duodenal bulb.

- Chronic watery diarrhea that improves with acid suppression.

- Markedly thick gastric folds on endoscopy.

- Personal/family history of MEN1 (parathyroid, pituitary, and pancreatic/duodenal tumors).

Quick reality check: long‑term PPIs are often essential in ZES. Yes, they raise gastrin, but they also prevent bleeding and perforation. In this condition, the benefit is not subtle.

Here’s a fast look at the key tests and what they tell you. Keep in mind, test availability can vary by country and center.

| Test | What it checks | Prep | Typical ZES result | Common pitfalls |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fasting serum gastrin + gastric pH | Confirms hypergastrinemia with acid in the stomach | Fast 6-8 hrs; if safe, stop PPIs 5-7 days, bridge H2 blockers | Gastrin often >1000 pg/mL with pH < 2 is highly specific | PPIs raise gastrin; atrophic gastritis and H. pylori can also elevate gastrin but typically with higher pH |

| Secretin stimulation test | Provokes gastrin release in gastrinoma | Hold PPIs if safe; done in specialized centers | Rise in gastrin ≥120 pg/mL above baseline | Limited availability; false positives with G‑cell hyperplasia |

| Upper endoscopy (EGD) | Ulcers, thick folds, biopsy for H. pylori, rule out other causes | Standard fasting | Multiple/atypical ulcers, hypertrophic folds | Findings are supportive, not diagnostic alone |

| Somatostatin receptor PET/CT (68Ga or 64Cu DOTATATE) | Localizes primary and metastases; assesses SSTR expression | None specific; renal function checked for PRRT planning | High uptake in gastrinomas and involved nodes/liver | Very small duodenal tumors may still be missed |

| Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) | Detects small pancreatic/duodenal lesions; guides biopsy | Fast; sedation | Localizes sub‑cm lesions; sample for pathology | Operator dependent; duodenal primaries can still be elusive |

| Multiphasic CT/MRI liver/pancreas | Staging; arterial phase helps spot NETs | Standard imaging prep | Highlights hypervascular tumors, liver mets | Small duodenal primaries may hide; use with EUS and PET |

| MEN1 labs/genetics | Calcium/PTH, prolactin, IGF‑1; MEN1 gene testing | None specific; genetic counseling advised | Identifies MEN1; shifts management and family screening | Not all patients need testing; target those with risk factors |

Quick example: a 36‑year‑old with recurrent ulcers despite high‑dose PPI and daily watery diarrhea. Gastrin is 1,500 pg/mL with gastric pH 1.4. DOTATATE PET lights up a 9 mm duodenal focus and a peripancreatic node. That patient likely benefits from surgical exploration after stabilizing acid.

Clinical guidance here tracks with major sources: NCCN (Neuroendocrine and Adrenal Tumors, 2024), ENETS guidance (2023), ACG guidance on gastric acid disorders (2022), and ESMO neuroendocrine tumor recommendations.

Diagnosis and Staging: A Practical Playbook

The fastest way to a confident diagnosis is to lock down two things: there’s too much gastrin, and the stomach is actually acidic. High gastrin alone isn’t enough, because atrophic gastritis and long‑term PPIs can spike it. Pair it with a low gastric pH and the picture sharpens.

- Stabilize first if there’s bleeding or severe pain. Don’t stop PPIs in a crisis. Bleeding or perforation risk beats testing purity every time.

- Plan testing windows. If the patient is stable, many centers pause PPIs 5-7 days before fasting gastrin and gastric pH, using H2 blockers as a bridge and stopping H2 blockers 24-48 hours prior. This must be individualized by the treating clinician.

- Get the core labs. Fasting gastrin with gastric pH. If gastrin is borderline (say 150-1000 pg/mL) but pH is low, a secretin stimulation test can clinch it.

- Scope smart. Upper endoscopy checks for ulcers, thick folds, and H. pylori, and documents baseline severity.

- Localize and stage. Use DOTATATE PET/CT plus multiphasic CT or MRI. Add EUS if pancreatic or small duodenal lesions are suspected or if biopsy would change management.

- Check for MEN1 when the story fits. Anyone with a family history of MEN1, multigland disease, early onset, or multiple pancreatic/duodenal NETs deserves a MEN1 workup (calcium/PTH, prolactin, IGF‑1) and a genetics chat.

Decision cues you can use:

- Gastrin >1000 pg/mL + pH <2 is basically diagnostic in the right clinical setting.

- Gastrin 150-1000 pg/mL + pH <2 → consider a secretin test if available.

- Elevated gastrin + pH >4 → think atrophic gastritis or prior gastric surgery; rethink ZES.

- Chromogranin A can support the picture but is often distorted by PPIs and kidney function.

How aggressive should localization be before the first operation? For sporadic disease, finding the primary matters-removing a tiny duodenal tumor and nearby nodes can be curative. Surgeons may do a careful duodenotomy with palpation and intraoperative ultrasound when imaging is equivocal. In MEN1, primaries are often multiple; surgery aims to control disease burden, not just “find the one.”

What should you bring to your first specialist appointment?

- A complete medication list, especially acid meds and doses.

- Every lab that mentions gastrin, gastric pH, chromogranin A, calcium, PTH, prolactin, and IGF‑1.

- All imaging reports and actual images (CT/MRI/EUS/PET).

- Endoscopy reports and photos.

- Family history of endocrine tumors, kidney stones, pituitary issues, or hypercalcemia.

Pitfalls to avoid:

- Stopping PPIs without a plan in someone with active ulcers-dangerous.

- Relying on chromogranin A alone.

- Skipping MEN1 checks in a young patient or one with suggestive family history.

- Assuming a negative scan rules out a duodenal primary-these can be tiny.

Two quick case sketches:

- Sporadic ZES, localized. A 48‑year‑old with gastrin 2,200 pg/mL, pH 1.2, DOTATATE PET shows a 7 mm duodenal focus and a single peripancreatic node. After pre‑op acid control, surgery finds a 6 mm duodenal tumor; node positive; margins clear. Long‑term PPI dose tapers down; surveillance imaging stays clean for years.

- MEN1‑related ZES, multifocal. A 30‑year‑old with hypercalcemia and multiple small duodenal lesions on EUS/PET. Surgery focuses on controlling disease (enucleations/limited resections and nodal dissection), not radical pancreatic surgery at first pass. Ongoing MEN1 surveillance continues for parathyroid and pituitary disease.

Treatment, Follow‑Up, and Daily Life

Management splits into two tracks: control the acid to protect the gut, and control the tumor to prevent spread and symptoms. Your team tunes both tracks over time.

Acid control

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs): High doses are standard in ZES-think omeprazole 60-120 mg/day (or an equivalent PPI), often in divided doses. The goal is to keep the gastric pH above ~3-4 most of the day. Doses adjust to symptoms and pH, not “standard GERD” dosing.

- H2 blockers: Useful as add‑ons at night or as temporary bridges during testing. Not strong enough alone long term in most ZES cases.

- Somatostatin analogs (octreotide/lanreotide): Can reduce gastrin secretion and acid output in some patients and treat tumor‑related symptoms. Also used for tumor control (see below).

What about PPI safety? Long‑term PPI use has been linked to low magnesium, low B12, bone density loss, and kidney issues in observational data. In ZES, the risk of uncontrolled acid beats these concerns. Your team can check magnesium and B12 yearly, consider bone health support, and keep an eye on renal function.

Tumor control

- Surgery (when localized): Goal is cure or durable control. For sporadic duodenal primaries, surgeons often perform a duodenotomy to find and remove tiny tumors and do a targeted node dissection. Pancreatic primaries may be enucleated or resected based on size and location. Whipple procedures are reserved for select cases; the bar is high.

- MEN1 nuance: Because lesions are multiple and recur, extensive pancreatic surgery early on can cause more harm than good. The strategy usually favors limited resections and careful follow‑up, unless there’s a dominant, higher‑risk lesion.

- Somatostatin analogs (SSAs): Octreotide LAR or lanreotide can slow growth in well‑differentiated neuroendocrine tumors and help with hormone‑driven symptoms. Doses are standard (e.g., octreotide LAR 20-30 mg IM q4 weeks; lanreotide 120 mg deep SC q4 weeks) and adjusted if disease progresses.

- Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT): If the tumor lights up on DOTATATE, PRRT with 177Lu‑DOTATATE is an option for progressive, metastatic, well‑differentiated disease. Evidence for NETs is strong, and gastrinoma patients benefit when criteria fit.

- Targeted therapies: Everolimus and sunitinib have proven benefit in pancreatic NETs, which includes many gastrinomas. These drugs can stabilize disease; side effects are real but manageable with experienced teams.

- Chemotherapy: CAPTEM (capecitabine + temozolomide) is widely used for pancreatic NETs and often active in gastrinoma. Streptozocin‑based regimens are older alternatives.

- Liver‑directed therapy: For liver‑dominant metastases, embolization, chemoembolization, or radioembolization can bring symptoms and growth under control.

How do we put that together in real life?

- Localized, sporadic ZES: High‑dose PPI → map the tumor with PET/CT + CT/MRI ± EUS → surgery to remove primary and involved nodes → taper PPI if safe → surveillance.

- MEN1‑related ZES: High‑dose PPI → MEN1 evaluation (parathyroids first; treat hypercalcemia because it worsens gastrin) → targeted surgery if there’s a dominant lesion or complications → long‑term SSAs if needed → surveillance of all MEN1 targets.

- Metastatic disease: High‑dose PPI + SSA → if progression and SSTR‑positive, consider PRRT → if still progressing, targeted therapy (everolimus/sunitinib) or CAPTEM → liver‑directed therapy for liver‑heavy disease → clinical trials where available.

Follow‑up schedule (typical ranges; your team will tailor it):

- Symptoms and meds: every 3-6 months, sooner if unstable.

- Labs: magnesium, B12 annually on PPIs; gastrin/pH as needed to guide dosing; MEN1 labs per protocol when relevant.

- Imaging: every 6-12 months if there’s residual or metastatic disease; after curative surgery, intervals vary by risk and grade.

- Endoscopy: intervals depend on ulcer history and symptoms; more often early, then stretch out if stable.

Daily life tips and pitfalls

- Take PPIs consistently, ideally before meals as directed.

- Avoid NSAIDs where possible; talk to your team about safer pain options.

- Hydration and small, simple meals help when diarrhea flares. Bile binders or pancreatic enzymes sometimes help if there’s malabsorption; ask your clinician.

- Flag black stools, vomiting blood, severe belly pain, or sudden fainting-these need urgent care.

- If planning pregnancy, involve your team early to review meds and timing.

Quick mini‑FAQ

- Is ZES just severe reflux? No. It’s a hormone‑driven acid problem from a tumor. Reflux is a symptom; the driver is gastrin.

- Do PPIs make gastrin go higher? Yes, and that’s expected. The goal is to keep acid at safe levels. In ZES, PPIs treat the damage while tumor‑directed therapy tackles the source.

- Can surgery cure ZES? Often in sporadic, localized disease. Less often in MEN1 because of multiple primaries. Cure rates depend on finding and removing the true primary and nodes.

- Do I need genetic testing? If you’re young, have multiple pancreatic/duodenal lesions, high calcium, or a family history of endocrine tumors, a genetics consult is wise.

- How often are scans needed? Every 6-12 months if you have active disease. After curative surgery and low‑grade tumors, intervals can be longer.

- Is PRRT safe? It’s effective for many SSTR‑positive NETs. Side effects include fatigue, nausea, and rare marrow or kidney effects. Pre‑treatment kidney checks and long‑term monitoring are standard.

- Can diet fix this? Diet helps symptoms, not the tumor. Focus on avoiding triggers and protecting the gut while medical and surgical treatments do the heavy lifting.

A few pro moves for patients and carers

- Keep a one‑page summary of your diagnosis, key scans, current meds, and allergies. Take it to every appointment.

- Ask, “What’s the primary goal right now-acid control, tumor control, or both?” It clarifies trade‑offs.

- On PPIs long term? Add magnesium and B12 checks to your yearly labs. Discuss calcium/vitamin D and bone health if you have other risk factors.

- Before stopping PPIs for testing, get a written plan with a 24/7 contact number in case symptoms get dangerous.

- For MEN1, set reminders for parathyroid and pituitary checks. Hypercalcemia can worsen ZES symptoms; treating it often helps.

Next steps and troubleshooting by scenario

- Newly diagnosed, high gastrin, ulcers active: Don’t rush to stop PPIs. Stabilize ulcers first. Book DOTATATE PET/CT and high‑quality pancreatic/duodenal imaging. If surgery is likely, meet the HPB surgeon early.

- Borderline gastrin, unclear pH: Repeat fasting gastrin with gastric pH under safe, supervised PPI taper. If still unclear and available, do a secretin test.

- MEN1 suspected: Check calcium/PTH first and treat hyperparathyroidism if present; it can reduce gastrin levels. See genetics to plan testing and family steps.

- Metastatic, SSTR‑positive, slow growth: Start SSA; consider PRRT at first signs of progression. Keep an eye on kidney function and blood counts in PRRT planning.

- Metastatic, SSTR‑negative or fast growth: Discuss CAPTEM or targeted therapy earlier. Ask your team how Ki‑67 grade is shaping the plan.

- Persistent diarrhea despite acid control: Rule out small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, pancreatic insufficiency, and bile acid diarrhea. Short trials of antibiotics, enzymes, or bile binders can be diagnostic and therapeutic.

Where does this guidance come from? It aligns with leading references: NCCN Neuroendocrine and Adrenal Tumors (2024), ENETS guidance (2023), ACG clinical guidance on acid hypersecretion (2022), and key NET trials supporting PRRT, everolimus, sunitinib, and CAPTEM in pancreatic/duodenal NETs. Your care should still be individualized by your team and your situation.

One last note: this is expert‑informed, people‑first information, not personal medical advice. If you’re alone and reading this at 2 a.m. because your pain is spiking, that’s your cue to seek urgent care. The right team makes this rare condition manageable-and for many, very treatable.

8 Comments

Zollinger‑Ellison syndrome requires a clear diagnostic algorithm and a team approach. The fasting gastrin level with gastric pH is the cornerstone test. Imaging with DOTATATE PET/CT or EUS helps locate tiny primaries. High‑dose PPIs are essential to protect the gut while you plan surgery.

It is an ethical imperative that clinicians abandon the reductive mono‑disciplinary model and embrace an interdisciplinary praxis replete with somatostatin‑receptor analytics. The moral obligation to engage endocrinology, oncology, and genetics under a unified protocol cannot be overstated. Anything less is a dereliction of professional duty.

Wow, look at the drama of it all! 🇺🇸 Our brave American patients wrestle with endless labs while the system stumbles over itself 😤. If only we could just dump the PPIs and call it a day – but no, the real battle is out there, and we’re all in it together! 💪

This guide reads like a textbook written for experts, not for the patients who actually have to live with the disease. The sheer amount of jargon makes it inaccessible, and the lack of plain‑language summaries is a glaring oversight.

Dialing back on acid seems essential.

Thank you for the thorough rundown! 😊 I really appreciate the reminder to check magnesium and B12 regularly – those little details can make a huge difference in quality of life. Keep the empathy flowing! 🙏

Ah, the glorious labyrinth of Zollinger‑Ellison management, where every specialist thinks they hold the holy grail of cure. First, let us applaud the notion that a patient can simply swallow a stack of PPIs and hope the tumor will vanish by sheer willpower. In reality, the acid hypersecretion is a relentless physiologic storm that demands calibrated pharmacology, not wishful thinking. High‑dose PPIs are not a cosmetic indulgence; they are a life‑saving bridge to any definitive therapy. Yet some clinicians persist in halting them for a “clean” gastrin draw, as if the ulcerated mucosa will not bleed in the interim. The secretin stimulation test, while elegant, is a luxury that only tertiary centers can afford, and its results are often misinterpreted by those who have never seen a gastrinoma. Imaging, too, is a saga: DOTATATE PET/CT will outshine an EUS for somatostatin receptor expression, but tiny duodenal lesions can still slip through the cracks of any scanner. Surgery, when possible, should be performed by a team that understands that duodenotomy and intra‑operative ultrasound are not optional theatrics but essential maneuvers. For MEN1 patients, the surgical script is rewritten; you cannot simply excise one node and declare victory. Multifocal disease demands a philosophy of disease control rather than radical cure, a nuance many “generalist” surgeons overlook. Post‑operative surveillance, contrary to popular belief, is not a yearly scan for fun, but a regimented schedule of gastrin assays, imaging, and endoscopy dictated by Ki‑67 grade. And let us not forget the silent contributors: magnesium, B12, and bone density, which are often sacrificed on the altar of long‑term PPI therapy. The multidisciplinary board should meet quarterly, not annually, to recalibrate therapy as the tumor’s biology evolves. If you ever doubt the value of a dietitian, remember that diarrhea can masquerade as disease progression, leading to unnecessary chemotherapy. In sum, the care pathway is a meticulously choreographed dance, not a chaotic free‑for‑all, and anyone treating ZES without respecting each step is simply courting disaster.

Dear community, I would like to commend the thoroughness of the guide while also offering a few clarifications to ensure optimal patient outcomes. First, high‑dose proton pump inhibitors should be titrated to maintain a gastric pH above 3, and periodic monitoring of serum magnesium and vitamin B12 is advisable to mitigate long‑term deficiencies. Second, when a secretin stimulation test is unavailable, a repeat fasting gastrin measurement after a brief, supervised PPI taper can often provide sufficient diagnostic confidence. Third, for patients with suspected MEN1, screening should extend beyond calcium and PTH to include prolactin and IGF‑1 levels, given the propensity for multi‑gland involvement. Fourth, surgical planning benefits greatly from intra‑operative ultrasound, particularly for duodenal primaries that are sub‑centimeter in size. Fifth, peptide receptor radionuclide therapy should be considered early for SSTR‑positive metastatic disease, as it has demonstrated both symptomatic relief and radiographic response. Sixth, in the setting of progressive disease despite somatostatin analogs, the combination of capecitabine and temozolomide (CAPTEM) remains a cornerstone regimen with a favorable toxicity profile. Seventh, nutrition counseling is essential; patients often report improvement in diarrhea with the introduction of a low‑fat, low‑fiber diet and the use of pancreatic enzyme supplements when indicated. Eighth, regular multidisciplinary tumor board discussions, ideally on a quarterly basis, facilitate dynamic treatment adjustments based on evolving disease biology. Ninth, patients should be educated about alarm symptoms such as hematemesis, melena, or severe abdominal pain, which warrant immediate medical attention. Finally, a concise, one‑page summary of the patient’s diagnosis, current treatment regimen, and upcoming appointments can greatly empower patients and streamline communication among care providers.