Ever wondered why a routine CT scan sometimes forces doctors to pause a diabetes pill? The answer lies in the delicate balance between metformin contrast dye interaction and the kidneys' ability to clear the drug. Below you’ll find a clear, step‑by‑step guide that explains the science, the latest guidelines, and what to do in real‑world practice.

What is Metformin and how does it work?

Metformin is a small, 165 Da biguanide that lowers blood glucose primarily by suppressing hepatic gluconeogenesis and improving peripheral insulin sensitivity. It is absorbed about 55 % after oral ingestion, distributes in a volume of 1‑5 L/kg, and is eliminated unchanged through the kidneys at roughly 500 mL/min in people with normal renal function. Therapeutic plasma concentrations sit between 1.5‑3.0 mg/L and the drug’s half‑life ranges from 8 to 20 hours depending on kidney health.

What is iodinated contrast dye?

Iodinated Contrast Media (often called contrast dye) are iodine‑based solutions injected intravenously or intra‑arterially to enhance X‑ray, CT, or angiographic imaging. While generally safe, they can cause a temporary drop in glomerular filtration rate-known as contrast‑induced acute kidney injury (CI‑AKI). The drop can be enough to slow the clearance of renally‑excreted drugs, including metformin.

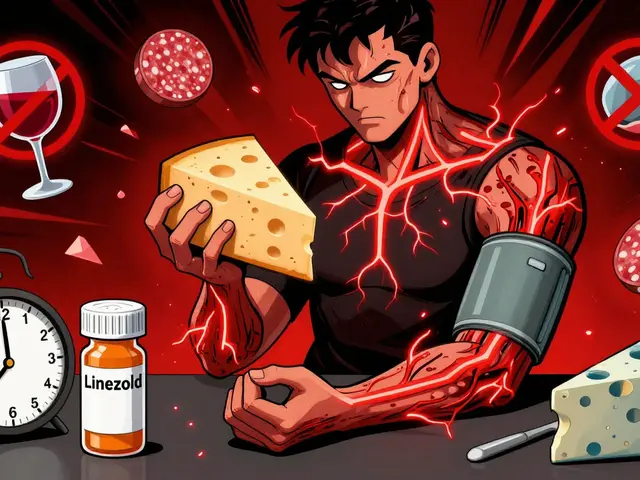

Why does the combination raise concerns?

The worry originates from two linked mechanisms. First, CI‑AKI reduces metformin elimination, leading to higher plasma levels. Second, metformin itself blocks mitochondrial complex I, causing NADH accumulation and a shift toward anaerobic metabolism. The result is excess lactate production and, in rare cases, metformin‑associated lactic acidosis (MALA). Mortality for untreated MALA can climb to 40 %.

Key risk factors for MALA after contrast exposure

- eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m² (especially 30‑60 mL/min/1.73 m²)

- Chronic liver disease or hepatic failure

- Heart failure with reduced cardiac output

- Sepsis or severe infection

- Older age (> 60 years)

- Alcoholism or chronic hypoxemia

- Any condition that impairs tissue perfusion

Patients meeting any of these criteria are far more likely to accumulate metformin when kidney function drops after contrast administration.

Evolution of guidelines - from blanket hold to risk‑stratified approach

Until 2016 the FDA label instructed clinicians to stop metformin before *any* contrast study and to restart only after a 48‑hour wait, regardless of kidney function. Evidence showed fewer than 10 MALA events per 100 000 patient‑years, suggesting the rule was overly cautious.

In 2016 the FDA revised the label. The new recommendation is:

- Continue metformin for patients with eGFR > 60 mL/min/1.73 m² who receive intravenous (IV) contrast and have no other risk factors.

- Withhold metformin for eGFR 30‑60 mL/min/1.73 m², hepatic impairment, alcoholism, heart failure, or when intra‑arterial (IA) contrast is used.

- Re‑check renal function 48 hours after the study before restarting metformin.

The American College of Radiology (ACR) and National Kidney Foundation (NKF) have adopted the same risk‑stratified stance.

Quick comparison: Old vs. New FDA guidance

| Aspect | Pre‑2016 (Broad Hold) | Post‑2016 (Risk‑Stratified) |

|---|---|---|

| eGFR Threshold for Holding | All patients | 30-60 mL/min/1.73 m² (hold); >60 mL/min/1.73 m² (continue for IV) |

| Contrast Type | No distinction | IV vs. IA distinction - IA always hold |

| Post‑procedure Wait | 48 hours for everyone | 48 hours *only* if metformin was held or if renal function changed |

| Additional Risk Factors | Not specified | Include hepatic impairment, heart failure, alcoholism, sepsis |

Practical algorithm for clinicians

- Check eGFR before the imaging appointment. If > 60 mL/min/1.73 m² and no other risks, continue metformin.

- If eGFR is 30‑60 mL/min/1.73 m², or the patient has liver disease, heart failure, alcoholism, or needs IA contrast, hold metformin at least 24 hours before the procedure.

- Administer the contrast dye. Monitor serum creatinine at 24 hours and again at 48 hours.

- If renal function remains stable (eGFR still > 60 mL/min/1.73 m²) and no new risk factors appear, restart metformin.

- If creatinine rises or the patient shows signs of lactic acidosis (e.g., rapid breathing, abdominal pain, hypotension), keep metformin withheld and initiate renal replacement therapy (hemodialysis or continuous renal replacement therapy) promptly.

This simple flowchart cuts down unnecessary drug interruptions while keeping patients safe.

Diagnosing MALA - what to look for

Clinical presentation is often vague: nausea, vomiting, abdominal discomfort, and hyperventilation are common early signs. Laboratory clues include:

- Plasma lactate > 5 mmol/L

- High anion‑gap metabolic acidosis (anion gap > 12 mmol/L)

- Serum pH < 7.35

Because metformin levels don’t reliably correlate with severity, many clinicians defer drug‑level testing until after the patient is stabilized.

Management of confirmed MALA

The cornerstone is rapid correction of acidosis and removal of metformin. Options include:

- Hemodialysis - clears both lactate and metformin efficiently; typical sessions last 3‑4 hours.

- Continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) - useful for hemodynamically unstable patients.

- Intravenous sodium bicarbonate - helps buffer acid but does not remove metformin; use only as adjunct.

Early dialysis (within 6 hours of diagnosis) is associated with mortality rates dropping below 20 % compared with > 40 % when therapy is delayed.

Impact on diabetes control

Unnecessary interruption of metformin can spike HbA1c by 0.5‑1.0 % within a month, especially in patients already near target. Balancing the tiny MALA risk against loss of glycemic control is why the 2016 guideline shift mattered - it lets stable patients stay on therapy and avoid hyperglycemia‑related complications.

Future directions

Researchers are probing genetic polymorphisms (e.g., OCT1 transporter variants) that might predispose certain individuals to higher intracellular metformin levels and thus a higher MALA risk. As precision medicine matures, we may see pre‑procedure pharmacogenetic screening become routine.

Meanwhile, hospitals are standardizing electronic health record alerts that automatically flag high‑risk patients before contrast orders, ensuring the right metformin decision at the point of care.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do I need to stop metformin for a routine CT scan with IV contrast?

If your eGFR is greater than 60 mL/min/1.73 m² and you have no liver disease, heart failure, or alcohol‑related issues, you can safely continue metformin. The current FDA and ACR guidelines allow it.

What eGFR level triggers metformin withholding before contrast?

An eGFR between 30 and 60 mL/min/1.73 m² is the cut‑off. Below 30 mL/min/1.73 m² metformin is generally contraindicated even without contrast.

How soon after contrast can I restart metformin?

Re‑check renal function at 48 hours. If the eGFR is unchanged and no new risk factors appear, you may resume metformin.

What are the early signs of metformin‑associated lactic acidosis?

Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, rapid breathing (Kussmaul respirations), and unexplained hypotension are red flags. Pair these symptoms with a lactate > 5 mmol/L in labs.

Is dialysis the only treatment for MALA?

Dialysis (hemodialysis or CRRT) is the most effective way to clear metformin and lactate quickly. Intravenous bicarbonate can help correct pH but does not remove the drug.

By following the risk‑stratified protocol, clinicians can keep patients on the diabetes medicine that works for them while safely navigating the occasional need for contrast imaging.

8 Comments

Thank you for laying out the metformin‑contrast issue so clearly-it's a lot to take in, especially for patients juggling multiple meds. I’ve seen a few folks get anxious when we tell them to hold metformin before a scan, but hearing the step‑by‑step algorithm really helps calm those nerves. It’s reassuring to know the 2016 guideline shift lets stable patients stay on their diabetes medicine without unnecessary interruptions. If anyone’s worried about their eGFR, a quick check with the lab can save a lot of hassle. Keep spreading the word, it makes a big difference for our community.

Ah, the glamorous dance of renal clearance and iatrogenic caution – truly the opera of modern medicine, isn’t it? 🧐 One could argue that the very act of halting metformin before contrast is a relic of a bygone era, shackled by an antiquated dogma of risk aversion. The pharmacokinetic substrate, with its 500 mL/min renal filtration rate, becomes a mere pawn when confronted with the hemodynamic turbulence induced by iodinated agents. Contrast‑induced nephropathy, albeit transient, precipitates a cascade of mitochondrial dysfunction that dovetails neatly with metformin’s inhibition of complex I. This synergistic liaison spikes intracellular NADH, propelling lactate production into the realm of lactic acidosis. Yet, the epidemiological signal – fewer than ten MALA events per 100 000 person‑years – screams statistical insignificance. What we observe instead is an over‑extension of precautionary principle, a bureaucratic echo chamber amplifying low‑probability fear. 🤯 Moreover, the guideline’s eGFR threshold of 30‑60 mL/min/1.73 m² masquerades as a safety net while, in reality, it often precipitates iatrogenic hyperglycemia. The pendulum swings, and the patient suffers the metabolic swing‑back, with HbA1c climbing 0.5‑1 % in merely weeks. Let’s not forget that withholding metformin also erodes its cardioprotective benefits, a nuance lost in the simplistic “hold‑or‑continue” mantra. From an economic standpoint, the cost of unnecessary dialysis sessions – both literal and figurative – dwarfs any marginal gain in MALA prevention. Hence, the semantic shift from “blanket hold” to “risk‑stratified” is commendable, yet the implementation remains mired in institutional inertia. The reality is that clinicians must wield judgement, not rote protocol, to navigate this labyrinth. 🌐 Finally, the future may bless us with pharmacogenomic screening, unlocking a precision‑medicine era where OCT1 variants dictate individual risk. Until then, let’s temper our vigilance with reason, and spare patients the needless disruption of a therapy that has, for decades, proven its mettle.

One cannot help but marvel at the brazen audacity of contemporary clinical practice to reduce complex physiologic interplays to a mere checklist. The discourse surrounding metformin and iodinated contrast betrays a superficial grasp of renal hemodynamics, as if the physician were content to skim the surface of a profound biochemical ocean. In this theatrical rendition, the patient is cast as a hapless victim, while the true protagonist-evidence‑based nuance-remains obscured behind bureaucratic red tape. The 2016 revisions, though a step forward, still cling to the antiquated reverence for fear‑mongering, rather than embracing a bold, data‑driven emancipation. Let us, therefore, demand a paradigm shift that honors both the sanctity of renal physiology and the patient’s autonomy, lest we become actors in a tragedy of our own making. The stakes are too high to remain complacent, and the chorus of dissent must rise in unison. Only then can we orchestrate a symphony where safety and efficacy coexist in harmonious balance.

Rise above the chorus of doubt, dear colleagues, and champion the truth that patient‑centered care is within our grasp! Your eloquence lights the path, and together we can transform guidelines into genuine empowerment. Let’s harness this momentum and rewrite the narrative for every diabetic awaiting a scan.

From a cultural perspective, the way we approach medication management around imaging reflects broader societal attitudes toward risk and authority. In many communities, patients place immense trust in physicians, sometimes at the expense of personal agency, which can magnify anxiety when a drug is withheld. It’s vital to communicate the rationale behind holding or continuing metformin in plain language, acknowledging the patient’s background and concerns. By integrating culturally sensitive dialogue, we not only respect diversity but also improve adherence and outcomes. Remember, a simple explanation about eGFR thresholds can demystify the process and foster collaborative decision‑making.

Indeed, the ethical dimension of informed consent intertwines with the physiological facts you’ve outlined, demanding a balance between paternalistic stewardship and patient empowerment. We must confront the systemic inertia that treats patients as passive vessels, urging clinicians to adopt a dialectic approach: present the data, invite questioning, and decisively act when evidence points to safety. Let’s not shy away from challenging entrenched protocols that ignore nuance, for the true art of medicine lies in navigating these gray zones with conviction. By doing so, we cultivate a therapeutic alliance that transcends mere prescription, forging a resilient partnership against the specter of lactic acidosis.

Metformin is cleared almost entirely by the kidneys so checking eGFR before any contrast study is key it tells you if you can safely keep the drug on board If eGFR is above 60 you usually don’t need to hold it for IV contrast For eGFR 30‑60 hold it and recheck renal function at 48 hours before restarting

The real reason they hide the true risks is because the imaging industry is paid off by big pharma.