Most people know opioids can cause constipation, drowsiness, or addiction. But there’s a far less talked-about danger: opioid-induced adrenal insufficiency (OIAI). It’s rare, but when it happens, it can be deadly. And doctors often miss it.

Imagine someone on long-term opioid pain medication - maybe after surgery, a chronic injury, or cancer treatment. They start feeling tired all the time, nauseous, dizzy, or faint when they stand up. They might lose weight without trying. At first, it looks like their pain is getting worse, or they’re just depressed. But what if their body isn’t making enough cortisol? That’s what OIAI does. It shuts down the stress response system your body needs to survive emergencies - like infection, surgery, or even a car accident.

How Opioids Quiet Your Stress Hormones

Your body’s stress response runs on a chain: the brain (hypothalamus) tells the pituitary gland to release ACTH, which then tells your adrenal glands to make cortisol. Cortisol is your natural emergency hormone. It keeps your blood pressure up, your blood sugar stable, and your immune system in check during stress.

Opioids - whether it’s oxycodone, hydrocodone, morphine, or methadone - interfere with this chain. They bind to receptors in the brain that dampen the signal from the hypothalamus and pituitary. Less ACTH means less cortisol. It’s not damage to the adrenal glands themselves. It’s a silent command being blocked.

Research shows this happens even with prescription opioids, not just street drugs. A 2023 study found about 5% of people in the U.S. on long-term opioid therapy have this issue. That’s hundreds of thousands of people. And it’s not just about high doses. One study found that patients taking more than 20 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per day had a much higher risk. Some studies show up to 22.5% of long-term users had signs of adrenal suppression, compared to 0% in people not on opioids.

How Do You Know If It’s Happening?

The problem? Symptoms look like everything else. Fatigue, nausea, low blood pressure, dizziness, muscle weakness - these are common in chronic pain patients. So doctors don’t always test for it.

But there’s a clear diagnostic path. If a patient on opioids has these symptoms, doctors should check morning cortisol levels. A level below 3 mcg/dL (or 100 nmol/L) is a red flag. To confirm, they do an ACTH stimulation test: give a synthetic version of ACTH and see if cortisol rises. A peak cortisol under 18 mcg/dL (500 nmol/L) after 30 or 60 minutes confirms adrenal insufficiency.

One case study followed a 25-year-old man who developed high calcium levels after a serious illness. Doctors ran tests and found his cortisol was dangerously low. He’d been on methadone for pain. Once they stopped the opioid and gave him hydrocortisone, his calcium normalized and his energy returned. His adrenal function came back after he stopped the drugs.

Why This Is So Dangerous

Cortisol isn’t just about feeling tired. It’s your body’s lifeline during stress. If you have OIAI and you get sick - say, with the flu, pneumonia, or even a minor infection - your body can’t respond. Your blood pressure crashes. You go into shock. You can die. This is called an Addisonian crisis.

And here’s the scary part: many patients don’t know they have it until they’re in the ER. One review of 27 studies with over 16,000 patients confirmed that opioid users had significantly worse quality of life - not just from pain, but from low energy, mood swings, and physical collapse. Their bodies were running on empty.

Even worse, some patients are on high-dose opioids for years without anyone checking their adrenal function. Pain clinics focus on pain control. Endocrinologists rarely get involved. So the condition flies under the radar.

Who’s at Risk?

- People on chronic opioid therapy for more than 90 days

- Those taking more than 20 MME per day

- Patients on methadone or buprenorphine (especially for pain, not just addiction treatment)

- Anyone with unexplained fatigue, weight loss, low blood pressure, or nausea on opioids

- People who’ve had recent hospitalizations or surgeries while on opioids

It’s not just cancer patients. One case report described a young man with chronic pancreatitis - no cancer, just persistent pain - who developed adrenal insufficiency after six months of daily opioids.

Can It Be Fixed?

Yes. And that’s the good news.

OIAI is reversible. When opioids are tapered slowly and stopped, cortisol production usually returns within weeks to months. In one case, a patient’s adrenal function fully recovered after 12 weeks off methadone.

But during the taper or if the patient gets sick, they need temporary glucocorticoid replacement - like hydrocortisone - to prevent crisis. Giving them extra cortisol during illness or surgery can save their life.

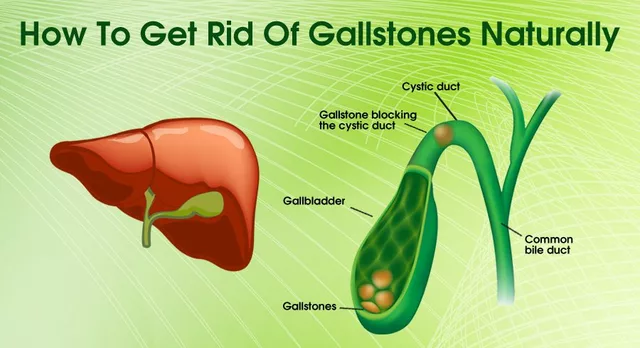

Importantly, opioids don’t affect aldosterone (the hormone that controls salt and potassium). So electrolyte imbalances are rare. This helps doctors rule out other forms of adrenal failure.

What Should You Do?

If you’re on long-term opioids and feel constantly worn out, dizzy, or nauseous - don’t assume it’s just the pain or depression. Ask your doctor to check your cortisol levels. If you’ve been on opioids for more than three months and are on more than 20 MME daily, request a simple morning cortisol test. It’s cheap, non-invasive, and could prevent a life-threatening event.

For doctors: screen patients on chronic opioids. Don’t wait for a crisis. A simple test can catch this early. And if you’re tapering someone off opioids, plan for adrenal support during the transition. You can’t assume their body will bounce back on its own.

This isn’t a theory. It’s a documented, preventable cause of death. And with over 5% of Americans on long-term opioids, we’re talking about a hidden public health blind spot.

Can opioid-induced adrenal insufficiency happen with short-term opioid use?

No, OIAI is almost always linked to long-term use - typically more than 90 days. Short-term use (like after surgery) doesn’t suppress the HPA axis enough to cause adrenal insufficiency. The problem builds over weeks to months as opioid receptors in the brain keep signaling the hypothalamus to reduce ACTH production.

Is opioid-induced adrenal insufficiency the same as Addison’s disease?

No. Addison’s disease is damage to the adrenal glands themselves, often from autoimmune disease. OIAI is different - the adrenal glands are fine. The problem is the brain isn’t telling them to work. It’s called secondary adrenal insufficiency. The fix is also different: in Addison’s, you need lifelong hormone replacement. In OIAI, stopping opioids often lets your body recover.

Do all opioids cause this?

Not equally. Most evidence points to stronger, longer-acting opioids like methadone, oxycodone, and morphine as the biggest culprits. Fentanyl and tramadol may carry lower risk, but data is limited. The key factor isn’t the specific drug - it’s the dose and duration. Higher daily doses (over 20 MME) and longer use (over 3 months) are the main drivers.

Can I just stop opioids if I suspect adrenal insufficiency?

No. Stopping suddenly can trigger withdrawal and worsen adrenal crisis. If you suspect OIAI, see your doctor. They’ll likely check your cortisol, then slowly taper the opioid while possibly adding short-term glucocorticoid support. Never adjust opioids on your own.

Are there any long-term effects if OIAI isn’t treated?

Untreated, it can lead to repeated adrenal crises, which are medical emergencies with high death rates. Even without full crisis, chronic low cortisol causes fatigue, poor stress tolerance, weight loss, and reduced quality of life. The longer it goes undiagnosed, the harder it is to recover fully, even after stopping opioids.

There’s no excuse anymore to ignore this. We know how it happens. We know how to test for it. We know how to treat it. The missing piece is awareness. If you’re on opioids long-term, ask. If you’re a clinician, screen. One simple blood test could save a life.

9 Comments