Every year, over 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generic drugs. They’re cheaper, just as effective for most people, and save the healthcare system billions. But sometimes, a doctor insists on the brand-name version - even when a generic is available. That’s not a mistake. It’s called a prescriber override, and it’s a legal tool built into state pharmacy laws to protect patients when generics aren’t safe enough.

Why Do Doctors Override Generic Substitution?

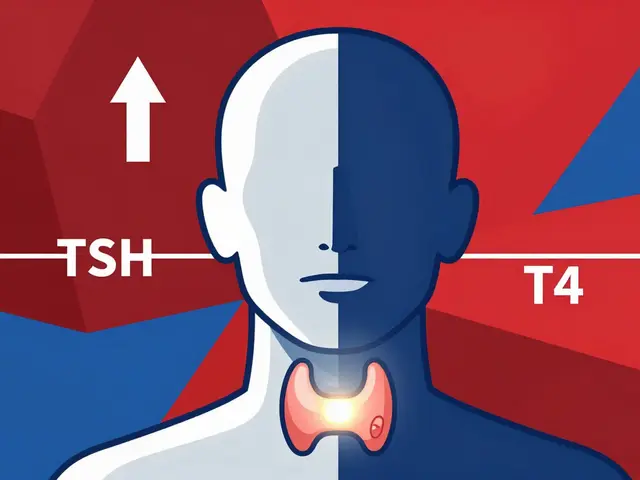

Generic drugs are required by law to have the same active ingredient, strength, and dosage form as their brand-name counterparts. But they can differ in fillers, dyes, coatings, and other inactive ingredients. For most people, that doesn’t matter. For others, it can be life-threatening. Take levothyroxine, a drug used to treat hypothyroidism. Even tiny differences in how the body absorbs different versions can throw thyroid levels out of balance. A patient stabilized on one brand might go into thyroid storm - a medical emergency - after switching to a generic. That’s not theory. The Institute for Safe Medication Practices documented 27 serious adverse events between 2018 and 2022 linked to improper substitution of levothyroxine, warfarin, or phenytoin. Other cases include patients with severe allergies to dyes or fillers in generics, or those who’ve tried multiple generics and had repeated therapeutic failures. In these situations, the doctor isn’t being stubborn. They’re protecting a patient who’s already been harmed by substitution.How Does a Prescriber Override Work?

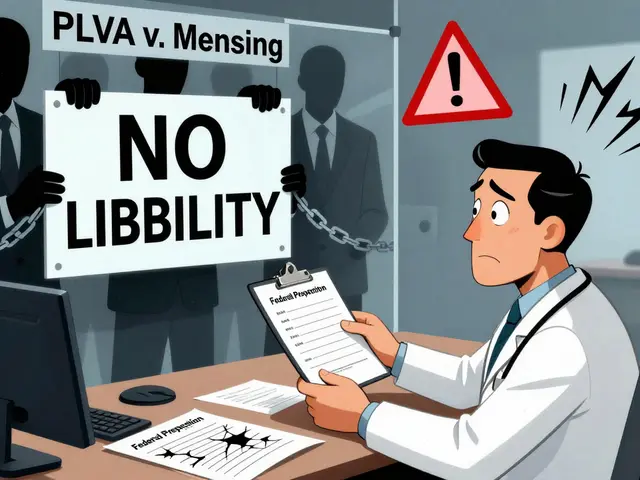

It all comes down to a code: DAW-1. That’s short for “Dispense as Written,” and it’s the only code that tells a pharmacist: Do not substitute. Give the brand. This code is sent electronically with the prescription or written by hand on paper. But here’s the catch - every state has its own rules for how it must be written. In Illinois, the doctor must check a box labeled “May Not Substitute.” In Kentucky, they must write “Brand Medically Necessary” by hand. In Massachusetts, “No Substitution” works. In Oregon, the prescriber can even call in the override. But in some states, if you write “Do Not Substitute” instead of the exact phrase required, the pharmacy system rejects it. No one gets the drug. The patient waits. The condition worsens. The National Council for Prescription Drug Programs (NCPDP) created the DAW code system to standardize this, but state laws haven’t caught up. As a result, doctors are forced to memorize 50 different sets of rules - or risk a patient being given the wrong medication.The Hidden Cost of Overrides

Generics saved the U.S. healthcare system $2.2 trillion between 2010 and 2019. That’s massive. But overrides cost money. On average, a DAW-1 prescription is 32.7% more expensive than a generic. In 2021, Express Scripts found that 18.4% of brand-drug spending was avoidable - caused by inappropriate overrides. Why? Because many doctors don’t know the rules. A 2010 survey found only 58.3% of physicians understood their own state’s override requirements. Some use the wrong wording. Some forget to check the box. Others assume their EHR system automatically adds DAW-1 when they write “brand preferred.” It doesn’t. And when that happens, the pharmacy dispenses the generic. The patient gets sick. The doctor gets blamed. Even worse, some doctors override out of habit - not necessity. Studies show physicians often overestimate how different generics are from brands. A 2019 analysis in JAMA Internal Medicine found that many doctors request brand-only dispensing for drugs where therapeutic equivalence is well-established. That’s not clinical judgment. That’s fear.State-by-State Chaos

There are 50 states. Each has its own law. Some require patient consent before substitution. Others assume consent unless the doctor says otherwise. Some allow pharmacists to substitute without telling the patient. Others require written notice. This patchwork creates real problems. A doctor who practices in both California and Nevada has to learn two different systems. An EHR system designed for Texas might not work in Michigan. A pharmacy in Arizona might reject a prescription from a New York doctor because the override wording doesn’t match their system. A 2022 poll on Sermo, a physician network, found that 63% of doctors struggled with inconsistent override rules. Forty-one percent said their electronic health records didn’t match their state’s requirements. Thirty-seven percent said pharmacies regularly misprocessed their override requests. One Reddit user, a general practitioner, shared a story from June 2023: a patient on levothyroxine was switched to a generic despite a DAW-1 override. The patient developed thyroid storm and was hospitalized. The pharmacy claimed the override wasn’t properly documented. The doctor had written “Brand Necessary” - but in that state, only “Brand Medically Necessary” was accepted. The system didn’t catch it. The patient nearly died.What Doctors Need to Do Right

If you’re a physician, here’s what you need to know:- Know your state’s exact wording requirement. Don’t guess. Check your state pharmacy board’s website.

- Use the DAW-1 code. Never rely on “brand preferred” or “no substitution” unless you’ve confirmed it’s accepted.

- Document the reason. “Patient allergic to dye” or “Therapeutic failure with two generics” gives the pharmacist context and protects you if questioned.

- Use your EHR’s override template - but verify it matches your state’s rules. Many are outdated.

- When in doubt, call the pharmacy. Ask: “Will this override work?”

The Future: Will This Get Easier?

The good news? Change is coming. The National Council for Prescription Drug Programs plans to integrate override requirements directly into the SCRIPT 201905 e-prescribing standard by late 2024. That means EHR systems will auto-populate the correct code based on the prescriber’s state. The FDA also updated its Orange Book in January 2023 to include biosimilar interchangeability ratings - a preview of how override rules may expand to biologic drugs like insulin and rheumatoid arthritis treatments. And there’s talk of federal legislation. The 2023 Standardized Prescriber Override Protocol Act, if passed, would create one national standard for DAW-1 documentation. That would end the state-by-state confusion. But until then, the burden falls on doctors. You’re not just writing a prescription. You’re navigating a legal minefield.

When Should You Override?

Not every case needs it. Here’s when you should:- The patient has a documented allergy to an inactive ingredient in generics.

- The patient has had repeated therapeutic failure with multiple generics (documented by lab results or symptoms).

- The drug has a narrow therapeutic index - levothyroxine, warfarin, phenytoin, digoxin, cyclosporine, or lithium.

- The patient is a child, elderly, or has multiple chronic conditions where stability is critical.

- You’ve never tried the generic on this patient.

- You’re just used to prescribing the brand.

- You’re worried about “quality” without evidence.

- The drug is not on the FDA’s Orange Book as therapeutically equivalent.

What Pharmacists See

Pharmacists aren’t the enemy. They’re caught in the middle. They want to save money. They also want to keep patients safe. A 2022 survey on AllNurses found that 68% of pharmacy claim rejections were due to improper override documentation. That’s not the doctor’s fault - it’s the system’s. But the pharmacist has to deny the claim. The patient gets angry. The doctor gets a call. The best pharmacies now use automated alerts: “Prescriber Override Requested - Verify State Requirements.” They flag it. They call. They double-check. That’s the gold standard.Bottom Line

Prescriber override isn’t about resisting generics. It’s about protecting patients who need the brand. Used correctly, it’s a vital safety valve. Used carelessly, it wastes money and risks lives. The system is broken - not because of doctors or pharmacists, but because of 50 different sets of rules. Until federal standardization happens, the onus is on you: know your state’s law. Use the right code. Document the reason. And never assume the system got it right.Can a pharmacist refuse to honor a prescriber override?

Legally, no - if the override is properly documented. But if the documentation doesn’t meet state requirements (wrong wording, missing signature, unclear reason), the pharmacy may refuse to dispense the brand and contact the prescriber for clarification. Always use the exact language required by your state’s pharmacy board.

Are brand-name drugs always better than generics?

No. For 90% of medications, generics are identical in effectiveness and safety. The FDA requires them to have the same active ingredient, strength, and absorption rate. Differences in inactive ingredients rarely matter - except for a small subset of patients with allergies or narrow therapeutic index conditions.

What does DAW-1 mean on a prescription?

DAW-1 stands for “Dispense as Written” and means the prescriber has explicitly prohibited substitution. The pharmacist must fill the prescription with the brand-name drug exactly as written - even if a generic is available and cheaper.

Can patients request a brand-name drug even if the doctor didn’t override?

Yes. That’s called DAW-2. If a patient wants the brand and the doctor didn’t block substitution, the patient can ask the pharmacist to dispense the brand instead of the generic. The patient usually pays the difference in cost, and the insurance may not cover it unless prior authorization is granted.

How do I find my state’s override requirements?

Visit your state’s pharmacy board website. The National Association of Boards of Pharmacy (NABP) also offers an interactive map that updates quarterly with each state’s substitution and override rules. You can also call your state board directly - they’re required to help prescribers understand the law.

8 Comments

Okay but like… why is this even a thing?? I got my levothyroxine switched last year and I was fine, but my aunt had a seizure?? Like, how is this still a patchwork of chaos?? I’m just glad my pharmacist called my doctor before dispensing!!

So… you’re telling me… that in India, we don’t even have this problem?? Because generics are the ONLY option?? And we’re fine?? 😅 I mean… I’ve seen people take 3 different generics for the same thing and live… but then again… we don’t have 50 laws… we have ONE law: “pay less, survive.”

Let’s be real - this whole system is a joke. Doctors don’t know the rules because they’re too busy being overworked. Pharmacists are stuck playing legal detective. And patients? They’re the ones getting caught in the crossfire. The FDA doesn’t even regulate inactive ingredients properly. It’s not about safety - it’s about liability. Every doctor who writes ‘brand necessary’ is just covering their ass. And the system rewards that. Pathetic.

DAW-1 isn’t magic. It’s paperwork. If your EHR auto-fills ‘no substitution’ and your state requires ‘brand medically necessary’ - you’re not protected. Period. I’ve seen 3 patients hospitalized because their docs used the wrong phrase. Stop assuming. Check the state board website. Bookmark it. Print it. Tape it to your monitor. This isn’t hard. It’s just ignored.

They’re all just scared of lawsuits. That’s it. The ‘narrow therapeutic index’ thing is a smokescreen. If generics were really that dangerous, they’d be banned. But they’re not. Big Pharma just wants you to keep paying $500 for a pill that costs $2 to make. The whole override system is a money grab dressed up as patient safety. Wake up.

Thank you for writing this!! 🙌 I’m a nurse and I’ve seen the chaos firsthand. My mom’s on warfarin - we had to call 3 pharmacies before one actually understood the override. But when they finally got it right? She was stable for the first time in months. This isn’t about brand vs generic. It’s about clarity. And we need federal standards. ASAP. 💪

Interesting. In India, we have no such thing as DAW-1. We have no choice. And yet, our mortality rates for chronic conditions are not higher than yours. Perhaps the issue is not the generic - but the system that makes you believe you need a brand. Or perhaps… it’s the cost of malpractice insurance that makes you over-prescribe. Just a thought. 😊

I’m from the Philippines and we don’t have generics as regulated as you do - but we have a different problem: counterfeit meds. So I get why you need rules. But 50 different ones? That’s not protection. That’s bureaucracy on steroids. I hope the federal law passes. We need one standard. No more guessing. No more hospitalizations. Just clear, simple, safe rules. 🌍❤️