When you’re taking medication to control seizures, the last thing you want to worry about is harming your future child. But for women of childbearing age, this isn’t just a hypothetical concern-it’s a daily reality. Antiseizure medications (ASMs) can save lives by preventing dangerous seizures, yet some of them carry serious risks during pregnancy. Birth defects, developmental delays, and dangerous drug interactions aren’t rare side effects-they’re well-documented outcomes tied to specific drugs. The good news? Not all ASMs are equally risky, and better options exist today than ever before.

Which Seizure Medications Are Most Dangerous During Pregnancy?

Not all antiseizure drugs are created equal when it comes to pregnancy. Some have been used for decades with known dangers, while newer ones have shown much safer profiles. The most concerning drug is sodium valproate. Studies show that about 10% of babies exposed to valproate in the womb develop major physical birth defects-things like heart problems, cleft lip or palate, spinal cord issues, and microcephaly (a smaller-than-normal head size). That’s more than double the risk seen with other medications.

Valproate doesn’t just affect physical development. Children exposed to it before birth are also more likely to be diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). One large study found these children had nearly twice the risk of ADHD and over double the risk of ASD compared to those exposed to other seizure medications.

Other high-risk drugs include carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, and topiramate. These are linked to increased chances of heart defects, facial abnormalities, and growth delays. The risk with these drugs often goes up with higher doses. For example, taking more than 800 mg of carbamazepine daily during pregnancy significantly raises the chance of birth defects.

But here’s the critical point: these risks don’t mean pregnancy is impossible. Even with high-risk medications, over 90% of babies born to women with epilepsy are healthy. The key is choosing the right drug-and the right dose-before conception.

The Safer Alternatives: Lamotrigine and Levetiracetam

The landscape has changed dramatically over the past 20 years. Today, two medications stand out as the safest choices for women planning pregnancy: lamotrigine (Lamictal) and levetiracetam (Keppra). Multiple reviews, including one by the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), confirm these drugs carry the lowest risk of birth defects among all antiseizure medications.

A Stanford study tracking 298 children exposed to newer ASMs in the womb found no significant difference in verbal skills at age two compared to children of mothers without epilepsy. That’s huge. It means these drugs don’t appear to interfere with early brain development the way older ones do.

Even better, lamotrigine and levetiracetam are effective at controlling seizures in most people. Many women switch to one of these before getting pregnant-and stay on it throughout pregnancy-with excellent results. That’s why current guidelines from the American Epilepsy Society say: if you’re planning a pregnancy and you’re on valproate or another high-risk drug, talk to your doctor about switching before you conceive.

Why Uncontrolled Seizures Are Even More Dangerous

It’s easy to focus only on the risks of medication. But there’s another side to this story: uncontrolled seizures are deadly. A tonic-clonic seizure during pregnancy can cause oxygen loss, physical injury, premature labor, or even miscarriage. The mother’s life is at risk, and so is the baby’s.

Experts call this the "excruciating double bind." You need medication to stop seizures, but the medication itself might harm the baby. The truth? The risk of a major seizure during pregnancy is far greater than the risk from most modern antiseizure drugs.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the American Epilepsy Society both agree: never stop your seizure medication without medical supervision. Stopping suddenly can trigger status epilepticus-a life-threatening seizure that lasts minutes or longer. That’s a far greater danger than the medication itself.

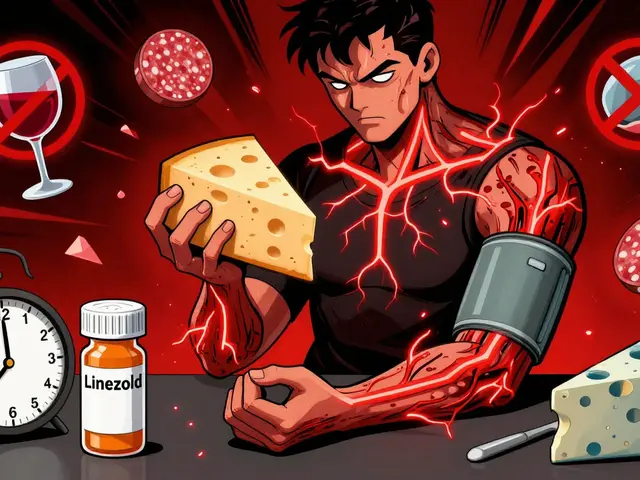

Drug Interactions: Birth Control and Seizure Meds Don’t Mix

Here’s something many women don’t realize: your seizure medication can make your birth control useless. And your birth control can make your seizure medication less effective. It’s a dangerous two-way street.

Drugs like carbamazepine, phenytoin, phenobarbital, oxcarbazepine, and high doses of topiramate speed up how your body breaks down hormones. That means birth control pills, patches, or rings may not work. Studies show women on these drugs are up to 30% more likely to get pregnant unintentionally.

On the flip side, hormonal birth control can lower the blood levels of lamotrigine, valproate, zonisamide, and rufinamide. If lamotrigine drops too low, seizures can return. That’s why women on lamotrigine often need higher doses during pregnancy-or when using hormonal contraception.

This isn’t just a minor issue. It’s a critical part of planning. If you’re sexually active and taking any ASM, you need to talk to your neurologist and gynecologist about your birth control options. Intrauterine devices (IUDs), especially non-hormonal ones, are often the safest bet. Implants can also work well. But pills, patches, and rings? They’re risky if you’re on certain seizure meds.

Who’s Most at Risk-and Why

Not everyone has the same access to safe care. A French study found that women with lower income, less education, or limited healthcare access were far more likely to be prescribed high-risk drugs like valproate during pregnancy. Why? Because they might not have seen a specialist. Or their doctor didn’t know the latest guidelines. Or they couldn’t afford to switch medications.

This isn’t about personal choices. It’s about systemic gaps. Even though the use of dangerous drugs has dropped by nearly 40% since 1997, the drop hasn’t been equal. Women in underserved communities still face higher exposure to valproate and phenobarbital.

That’s why preconception counseling matters so much. It’s not a luxury-it’s a necessity. If you’re a woman with epilepsy and you’re thinking about having a child, you need to see a specialist before you get pregnant. That’s when you can safely switch medications, adjust doses, and plan for monitoring.

What’s Changed Since the 1960s

It’s hard to believe now, but until the 1960s, women with epilepsy were often told not to marry or have children. Some U.S. states even passed laws banning marriage for people with epilepsy. The fear was based on stigma, not science.

Then came the first wave of antiseizure drugs-valproate, phenytoin, carbamazepine. They worked. But they came with hidden dangers. It took decades to understand how harmful they were to unborn babies.

Today, we know better. We have safer drugs. We have better monitoring. We have guidelines. The number of major birth defects linked to seizure meds dropped by 39% between 1997 and 2011, thanks to smarter prescribing and more awareness.

Still, there’s work to do. Eleven other antiseizure drugs haven’t been studied enough to confirm their safety in pregnancy. And too many women are still being prescribed high-risk drugs because no one asked the right questions.

What You Need to Do Now

If you’re a woman with epilepsy and you’re thinking about pregnancy-or even just sexually active-here’s what to do:

- See your neurologist before trying to conceive. Don’t wait.

- Ask: "Is my current medication safe during pregnancy?" If you’re on valproate, carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, or high-dose topiramate, ask about switching.

- Discuss birth control. If you’re on carbamazepine, phenytoin, or similar drugs, avoid pills, patches, or rings. Ask about IUDs or implants.

- Get your medication levels checked regularly, especially if you start or stop hormonal contraception.

- Take folic acid daily-4 mg if possible-starting at least three months before conception. It lowers the risk of neural tube defects.

You don’t have to choose between controlling your seizures and having a healthy baby. With the right plan, you can do both. The safest medications today are effective, well-studied, and available. You just need to start the conversation-and start it early.

Can I stop my seizure medication if I’m pregnant?

No. Stopping seizure medication suddenly can trigger dangerous seizures that put both you and your baby at risk. Always talk to your doctor before making any changes. Uncontrolled seizures are more dangerous than most antiseizure drugs.

Is lamotrigine safe during pregnancy?

Yes. Lamotrigine is one of the safest antiseizure medications for pregnancy. Studies show very low rates of birth defects and no major impact on child development. However, its levels drop during pregnancy, so your doctor will likely need to adjust your dose.

Can birth control pills interfere with my seizure meds?

Yes. Hormonal birth control can lower the effectiveness of lamotrigine, valproate, zonisamide, and rufinamide. This can lead to breakthrough seizures. If you’re on one of these drugs, you may need a higher dose or a different form of birth control, like an IUD or implant.

Does taking folic acid help reduce birth defects?

Yes. Taking 4 mg of folic acid daily for at least three months before conception significantly lowers the risk of neural tube defects like spina bifida. This is especially important for women taking antiseizure drugs, as these medications can interfere with folate metabolism.

Why is valproate still prescribed to some women?

Valproate is very effective for certain types of seizures, especially when other drugs fail. But because of its high risk of birth defects, guidelines now say it should be avoided in women of childbearing age unless no other option works. Some women may still be on it due to lack of access to specialists or outdated prescribing habits.

If you’re planning a pregnancy or already pregnant and taking seizure medication, don’t wait. Talk to your neurologist today. With the right plan, you can manage your seizures and have a healthy baby.

9 Comments

Been on lamotrigine for 8 years now and got my daughter through pregnancy just fine. No issues. Just make sure your doc knows to bump the dose when you're pregnant. I went from 150 to 300 by the third trimester. Worth it.

valproate is evil dont let them push it on you

It's wild how medicine evolves. We used to lock people up for epilepsy. Now we're fine-tuning drug cocktails so a woman can hold her baby without fear. Science isn't perfect but it's trying. 🤔

HOW IS THIS STILL A THING?! Women are getting prescribed VALPROATE like it's Advil. My cousin had a baby with spina bifida because her doctor didn't tell her. This is medical negligence wrapped in a white coat.

Let me just say this: if you're a woman with epilepsy, and you're thinking about having a child-PLEASE, PLEASE, PLEASE-schedule a preconception appointment with a neurologist who specializes in epilepsy and pregnancy. Don't wait. Don't assume your OB knows everything. Don't trust your last prescription. This is life-altering stuff. And folic acid? 4 mg daily. Start three months before. It's not optional. It's non-negotiable.

Also, if you're on carbamazepine or phenytoin and using the pill? You're basically playing Russian roulette with your fertility. Switch to an IUD. Now. IUDs don't care about your meds. They just work.

And if you're worried about lamotrigine dropping during pregnancy? That's normal. That's expected. Your doc should be monitoring levels every trimester. If they're not? Find a new one.

This isn't fear-mongering. It's empowerment. You can have a healthy baby. You can control your seizures. But you have to be the advocate. No one else will do it for you.

I switched from valproate to levetiracetam before trying for my son. Took a year to get the dose right but it was worth every sleepless night. He's 4 now and hitting all his milestones. No developmental delays. No issues. Just a kid who loves dinosaurs and peanut butter sandwiches.

Also-yes, birth control and seizure meds don't mix. I learned that the hard way. Got pregnant by accident once because I didn't know. Don't make my mistake.

why do women even want kids when they have seizures? its so selfish. what if the baby suffers? i think god gives us epilepsy so we dont reproduce. just my thoughts

My sister just had her second kid on lamotrigine. Doctor said she’s one of the safest options. Folic acid was her best friend. No drama. Just a healthy baby and a mom who finally felt heard.

Let’s be brutally honest here. The entire narrative around "safe" ASMs during pregnancy is a marketing-driven illusion. Lamotrigine and levetiracetam are only "safer" because they’ve been studied more recently and marketed aggressively by pharmaceutical companies. The data is still limited. We’re talking about neurodevelopmental outcomes over decades-not just birth defects at age two. The Stanford study? Tiny sample size. No long-term follow-up. And let’s not forget the placebo effect of hope. Women are being sold a dream wrapped in peer-reviewed jargon. Meanwhile, the real issue is systemic: women without access to specialists are being left behind, yes-but so are women who are told they "can have it all" when in reality, their seizure control might deteriorate postpartum, and their mental health collapses under the weight of impossible expectations. We’ve replaced one form of stigma with another: the expectation that you must be both perfectly seizure-free and perfectly maternal, all while your meds are being adjusted like a dial on a radio. And no one talks about the postpartum crash. No one talks about the fact that even "safe" drugs can cause neonatal withdrawal. No one talks about the guilt when a child develops a learning disability years later and you wonder if it was the lamotrigine. This isn’t empowerment. It’s a pressure cooker dressed up as a checklist.