Working out with diabetes doesn’t have to mean constant fear of crashing. But if you’ve ever felt shaky, sweaty, or dizzy halfway through a run-or woke up in the middle of the night with a pounding heart after a morning swim-you know how real the risk is. Exercise-induced hypoglycemia is one of the biggest reasons people with type 1 diabetes avoid physical activity altogether. The good news? It’s preventable. With the right strategy, you can move more, feel stronger, and stay safe.

Why Exercise Drops Your Blood Sugar

When you move, your muscles need energy. They don’t always wait for insulin to tell them how to get it. During exercise, your muscles pull glucose straight from your bloodstream-no insulin required. At the same time, your body becomes more sensitive to insulin, meaning even a small amount can work harder and longer than usual. That combo can send your blood sugar plummeting, sometimes hours after you’ve finished. This isn’t just a type 1 thing. People with type 2 diabetes on insulin or certain medications like sulfonylureas can also experience lows. But the risk is highest for those using insulin pumps or multiple daily injections. The American Diabetes Association says about half of adults with type 1 diabetes avoid exercise because they’re scared of going low. That’s not just inconvenient-it’s dangerous long-term. Regular activity improves insulin sensitivity, reduces heart disease risk, and helps manage weight. You don’t have to choose between safety and fitness.Check Before You Start

Don’t just guess your numbers. Check your blood glucose 15 to 30 minutes before you begin. That’s non-negotiable. Here’s what to do based on what you see:- Below 90 mg/dL: Eat 0.5 to 1.0 gram of carbs per kilogram of body weight. If you weigh 70 kg, that’s 35 to 70 grams of carbs. A banana, a granola bar, or 4 glucose tablets will do.

- Between 90 and 150 mg/dL: Eat 15 to 20 grams of fast-acting carbs. Think 3-4 glucose tabs, half a juice box, or 6 hard candies.

- Above 150 mg/dL: You’re likely good to go, especially if you’re doing moderate activity. But keep monitoring.

Timing Matters More Than You Think

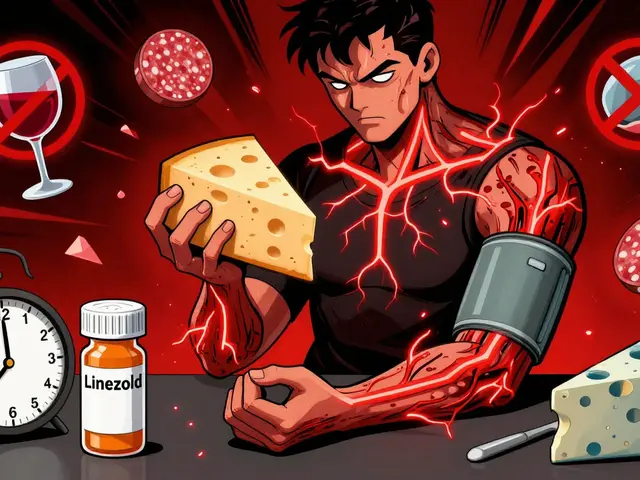

When you take insulin matters just as much as what you eat. If you’ve just given a bolus for lunch, don’t hit the treadmill right after. Peak insulin action usually happens 1 to 3 hours after eating. Exercising during that window is like pouring gasoline on a fire. Instead, aim for consistent times. If you always walk at 6 p.m., your body learns to expect it. Your insulin needs become predictable. If you’re on an insulin pump, consider reducing your basal rate by 50-75% starting 60 to 90 minutes before exercise. If you’re on injections, cut your pre-workout bolus by 25-50%. These aren’t guesses-they’re evidence-backed adjustments from the ADA’s 2023 guidelines. And don’t forget insulin-on-board (IOB). That’s the amount of active insulin still working in your body. If you have 2 units of insulin on board, and you’re about to run, that’s like having 3 or even 4 units of effect. Most pumps calculate this automatically. If you’re not using one, track your last bolus and its duration. When in doubt, lower your insulin or eat more carbs.Not All Workouts Are Created Equal

Here’s the surprise: not every type of exercise makes your blood sugar drop. In fact, some types can actually help keep it stable-or even push it up.- Aerobic exercise (running, cycling, swimming): Tends to lower glucose steadily. The longer and more intense, the bigger the drop.

- Resistance training (weight lifting, bodyweight exercises): Can raise or stabilize glucose. Muscles use stored glycogen, which triggers the liver to release more glucose.

- High-intensity intervals (sprints, HIIT bursts): Trigger adrenaline, which signals the liver to dump glucose. A 10-second all-out sprint before your workout can prevent a low for the next 30 minutes.

Use Your Tech-Smartly

If you use a continuous glucose monitor (CGM), you’re already ahead. But most people don’t use it to its full potential. Dexcom’s G7 and Abbott’s FreeStyle Libre now have built-in “exercise modes” that lower alert thresholds during activity. That means you’ll get warned earlier if your glucose is trending down. Check your CGM every 30 minutes during exercise. Don’t wait for an alarm. Look at the trend arrow. Is it pointing down fast? Eat carbs now, not when you hit 65 mg/dL. Also, keep your CGM on overnight. Delayed hypoglycemia happens in 70% of people with type 1 diabetes after exercise. A nighttime low can be scary-or worse. Eat a bedtime snack with 15 grams of carbs and a bit of protein (like peanut butter on toast or Greek yogurt) if you exercised in the afternoon or evening.Real People, Real Results

On diabetes forums, people are sharing what works. One user on Reddit said he did the same 5K run three times in a row-with the same insulin dose-and got readings of 70, 180, and 120 mg/dL. Why? Stress, sleep, weather, even the time he ate dinner changed his response. That’s normal. Your body isn’t a machine. But here’s what helped others:- A woman in Sydney started doing 10-second sprints on her stationary bike before every walk. Her lows dropped from four times a week to once every two weeks.

- A man in Chicago switched from pure cardio to circuit training-30 seconds of squats, 30 seconds of push-ups, 30 seconds of jumping jacks, repeat. His average glucose during workouts went from 88 to 112 mg/dL.

- A teenager on an insulin pump set a 60% basal reduction before soccer practice. She went from missing two games a week to playing without a single low.

What to Carry (And What to Avoid)

Always have fast-acting carbs with you. Glucose tabs are best-they’re precise, portable, and fast. Avoid candy bars or cookies. They’re full of fat and fiber, which slow down absorption. You need glucose to hit your bloodstream in 10-15 minutes, not 45. Also carry a medical ID. And tell someone you’re working out. Even if it’s just a quick text: “Heading out for a 30-minute bike ride. Will check in after.”

It Gets Easier-But Not Overnight

Learning how your body reacts to movement takes time. UCLA Health says it usually takes 3 to 6 months of consistent tracking to really understand your patterns. Keep a log: what you did, how long, what you ate, your insulin dose, and your glucose before, during, and after. Look for trends. Did you go low after swimming but not after walking? Did a late lunch make your evening workout riskier? Don’t get discouraged by the bad days. Even the most experienced athletes with diabetes have off days. The goal isn’t to never go low. It’s to know how to catch it early, fix it fast, and learn from it.What’s Next? The Future Is Here

New tech is making this easier than ever. The Tandem t:slim X2 pump, approved in March 2023, uses machine learning to predict when exercise will drop your glucose-and automatically reduces insulin before it happens. Clinical trials of dual-hormone artificial pancreas systems (which deliver both insulin and glucagon) are showing a 52% drop in exercise-related lows. By 2026, these features will be standard. But you don’t need to wait. The tools you have now-CGMs, insulin pumps, smart tracking-are enough. You just need to use them with intention.Start Small. Stay Consistent.

You don’t need to run a marathon. Start with a 15-minute walk. Check your glucose. Eat if needed. See how you feel. Do it again tomorrow. Then add 5 minutes. Then try a set of bodyweight squats. Track it. Learn it. Own it. Exercise isn’t the enemy of diabetes. It’s one of the most powerful tools you have. The lows? They’re just a sign you’re doing something right-and that you need to tweak your plan a little. You’ve got this.Can I exercise if my blood sugar is below 70 mg/dL?

No. If your blood sugar is below 70 mg/dL, treat it first with 15 grams of fast-acting carbs (like glucose tabs or juice). Wait 15 minutes and check again. Only start exercising once your glucose is above 90 mg/dL and stable. Exercising while low can cause your sugar to drop even further, leading to dizziness, confusion, or loss of consciousness.

Do I need to eat carbs during long workouts?

Yes, if your workout lasts longer than 60 minutes and your blood sugar is trending down. For moderate activity, consume 0.5 to 1.0 gram of carbs per kilogram of body weight every hour. For example, a 70 kg person should aim for 35 to 70 grams of carbs per hour-think a banana, a sports drink, or a handful of gummies. Always carry carbs, even if you think you won’t need them.

Why do I go low hours after exercising?

After exercise, your muscles keep pulling glucose from your blood to refill their stores. This can last up to 24 to 72 hours. Your insulin sensitivity stays higher, too. That’s why nighttime lows are common after afternoon workouts. To prevent this, check your glucose before bed. If it’s below 120 mg/dL, eat a small snack with carbs and protein-like a piece of toast with peanut butter or a cup of Greek yogurt.

Should I reduce my insulin before working out?

If you use insulin, yes-especially if you’re doing moderate or prolonged aerobic activity. For insulin pump users, reduce your basal rate by 50-75% starting 60-90 minutes before exercise. For those on injections, reduce your pre-workout bolus by 25-50%. Always calculate your insulin-on-board first. If you have a lot of active insulin, you’ll need a bigger reduction.

Is it safer to lift weights than to run?

Generally, yes. Resistance training (like weight lifting) tends to raise or stabilize blood glucose because it triggers the liver to release stored sugar. Aerobic exercise like running or cycling is more likely to cause a drop. But the safest approach is to combine both: do 15-20 minutes of strength training before your cardio session. Studies show this cuts glucose drops by nearly half.

Can I use a CGM to predict lows during exercise?

Yes, modern CGMs like Dexcom G7 and FreeStyle Libre 3 have exercise modes that adjust alert thresholds and trend predictions during physical activity. They can warn you 15-20 minutes before a low is likely to happen. Use the trend arrow-not just the number. If it’s pointing down sharply, act before you feel symptoms.

What’s the best snack to eat before a workout?

Choose fast-acting carbs with little to no fat or fiber. Good options: 4 glucose tabs, half a banana, 6 ounces of regular soda, or 1/2 cup of applesauce. Avoid chocolate bars, trail mix, or granola bars-they’re too slow to raise your blood sugar when you need it fast.

Should I avoid exercise if I’m sick?

If you have ketones or your blood sugar is over 250 mg/dL, avoid exercise. Your body is under stress and needs insulin, not extra energy demands. Even if your sugar is normal, if you’re feverish or fatigued, rest. Exercising while sick can worsen insulin resistance and increase the risk of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA).

10 Comments

Just did a 45-minute bike ride after a light snack and my CGM showed me dropping hard-trend arrow screaming down like a rollercoaster about to loop. I threw down 4 glucose tabs and kept pedaling. No crash. No panic. Just smart prep. This post? Gold.

Let me tell you something-I’ve been living with type 1 for 22 years, and I used to avoid exercise like it was a death sentence. Then I started tracking everything: insulin on board, meal timing, sleep quality, even the damn weather. Turns out, my body doesn’t hate movement-it hates unpredictability. So now I do the same workout at the same time, same carb intake, same basal adjustment. Consistency is the real hack. And yeah, I still go low sometimes, but now I catch it before it catches me. The 10-second sprints before cardio? That’s not a trick, it’s biology. Your liver’s got your back if you give it a heads-up. Also, stop eating granola bars before runs. They’re basically candy-coated bricks. Glucose tabs are your new best friend. And if you’re not using your CGM’s exercise mode? You’re leaving money on the table. It’s not magic, it’s data. Use it.

THIS. 🙌 I did my first weight session before swimming last week and didn’t have a single low. I cried. Not because I was low, because I was FREE. Thank you for writing this. 💪❤️

So let me get this straight-you’re telling me I don’t have to suffer through a 6am run with a juice box in my pocket like some diabetic monk? And I can just… lift weights first? And my pump will magically adjust? Who gave you a medical degree? 😏

There’s something beautiful about how our bodies adapt when we stop fighting them. I used to see lows as failures. Now I see them as feedback. Like my body whispering, ‘Hey, you forgot to eat after that meeting, didn’t you?’ It’s not perfect. It’s not linear. But it’s mine. And I’m learning to listen-not just manage. That’s the real win.

My pump crashed during a hike. I’m never trusting tech again.

Living in London, I’ve learned that rain, wind, and a 7am tube ride all mess with my glucose like a chaotic orchestra. I used to blame myself. Now I blame the British weather and call it a day. I’ve started doing 15 minutes of yoga before my morning walk-calms the nerves, stabilizes the numbers, and I don’t feel like I’m being punished for wanting to move. Also, peanut butter on toast before bed? My nighttime lows vanished. I swear by it. You don’t need fancy gadgets. You just need to know your rhythm. And maybe a warm blanket.

you know what they dont tell u? all this 'evidence based' crap is just big pharma selling u more pumps and cgm subscriptions. i had zero lows for 3 years before i got a cgm. now i get alerts for everything. i think they want us scared so we keep buying stuff. carbs? just eat a burger. insulin? just skip it. its all lies.

I get where Jeffrey’s coming from-I really do. But I also remember the time I passed out on my bathroom floor after a morning run because I thought I ‘felt fine.’ Turns out, feeling fine doesn’t mean your glucose is fine. I used to think tech was overkill too. Now I’m grateful for every alert. I’m not buying into a system-I’m buying into safety. And if a little piece of tech helps me play with my nephew without panic? I’ll take it. No shame in using every tool you’ve got.

This entire article is a government mind-control scheme to get diabetics dependent on insulin pumps. The real cure is fasting and avoiding all carbs. Exercise is just a distraction from the truth. The ADA is funded by Big Pharma. You’re being manipulated.