When a new drug hits the market, it doesn’t just come with a price tag-it comes with a legal shield. Two shields, actually. One is called patent exclusivity. The other is market exclusivity. They sound similar, but they’re not the same. And the difference? It can mean the difference between a drug costing $10 a pill or $500. If you’ve ever wondered why some drugs stay expensive long after their patents expire, the answer isn’t just about big pharma-it’s about how the FDA and the patent office play different roles in keeping generics off the shelf.

Patent Exclusivity: What It Actually Protects

A patent is a legal right granted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). It doesn’t give you the right to sell a drug-it gives you the right to stop others from making, using, or selling it. The standard patent term is 20 years from the date you file it. Sounds straightforward, right? But here’s the catch: most drugs take 10 to 15 years just to get approved by the FDA. That means if you file your patent when you start developing the drug, you might only have 5 to 8 years of real market protection left after approval.

That’s why drug companies often rely on patent extensions. The law allows for Patent Term Extension (PTE), which can add up to 5 years to the patent life, but only if the delay was caused by FDA review. And even then, the total time a drug can be protected after approval is capped at 14 years. So if a drug gets approved 12 years after the patent was filed, the extension might only give you 2 extra years. It’s not magic-it’s math.

Patents can cover different parts of a drug: the active ingredient (composition of matter), how it’s made (process), how it’s packaged (formulation), or how it’s used (method of treatment). The strongest patent? The one on the chemical itself. But many companies file dozens of secondary patents-on pill coatings, dosing schedules, or delivery systems-to keep generics out longer. In fact, the FTC found that 68% of patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book are secondary, not the original composition patent.

Market Exclusivity: The FDA’s Secret Weapon

Now, here’s where things get interesting. Market exclusivity has nothing to do with patents. It’s granted by the FDA, not the patent office. And it doesn’t care if the drug is new or old. If you submit new clinical data to get approval, the FDA will block competitors from using that data to get their own versions approved-for a set period.

This is called data exclusivity. It’s not about copying your patent. It’s about copying your clinical trials. The FDA won’t let a generic company rely on your studies to prove safety or effectiveness. They have to do their own. And that’s expensive. So the FDA gives you a time window where they simply won’t approve a competitor, even if your patent is expired.

The most common type is New Chemical Entity (NCE) exclusivity: 5 years. During that time, the FDA can’t even accept an application from a generic maker. After 5 years, generics can apply-but they still can’t use your data for 4 more years. That’s 9 years of de facto protection. Then there’s orphan drug exclusivity: 7 years for drugs treating rare diseases, regardless of patent status. And pediatric exclusivity: 6 extra months if you test the drug on kids. It’s not a bonus-it’s a financial incentive. Since 1997, these pediatric extensions have generated about $15 billion in extra revenue for drugmakers.

Biologics? They get 12 years. That’s a whole different category. These are complex drugs made from living cells-like insulin or cancer treatments. They’re harder to copy than pills. The FDA doesn’t even call them “generics.” They’re called “biosimilars.” And even then, the 12-year clock doesn’t start until approval. So if a biologic takes 10 years to get approved, the company might have 2 years of market time before biosimilars can even enter.

When They Overlap (And When They Don’t)

Here’s the key: patents and market exclusivity can run at the same time. Or one can end while the other keeps going. The FDA says 27.8% of branded drugs have both. But 38.4% have only patents. And 5.2%? They have no patent at all-just exclusivity.

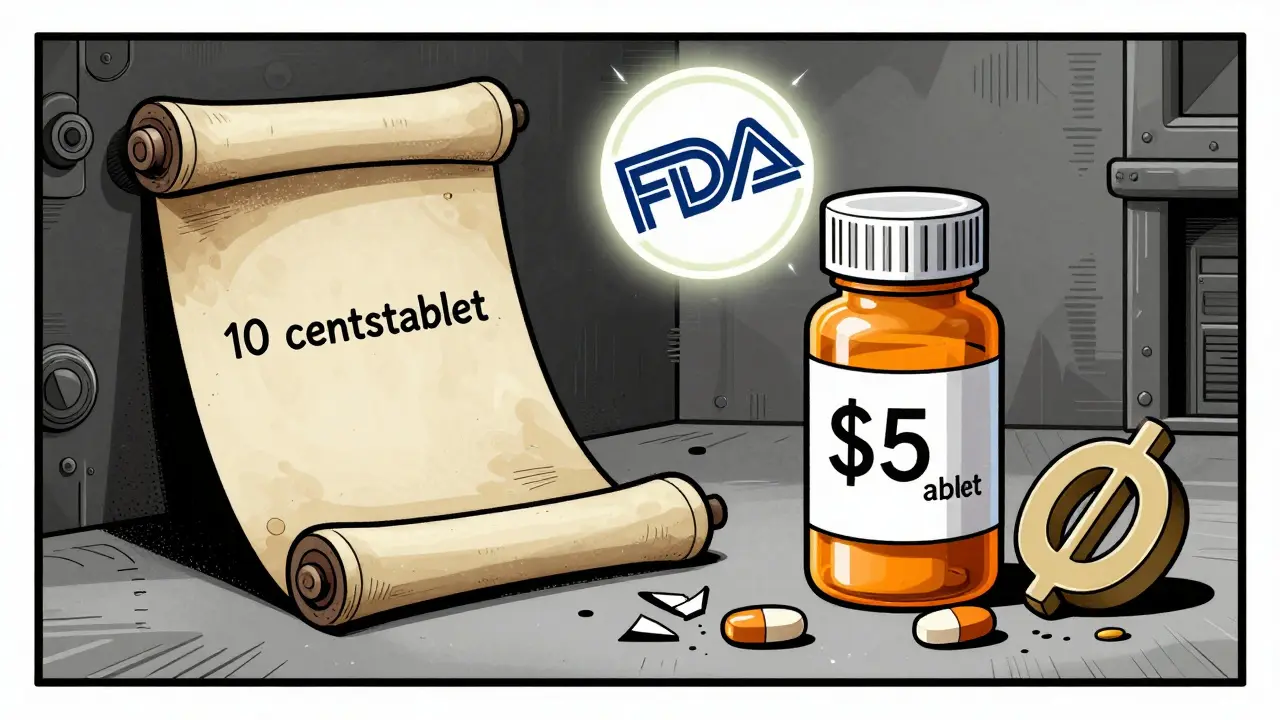

That last number is critical. It means the FDA is protecting drugs that aren’t even patentable. Take colchicine. It’s been used since ancient Egypt to treat gout. But in 2010, Mutual Pharmaceutical got FDA approval for a new formulation. They didn’t have a patent. But they submitted new clinical data. So the FDA gave them 10 years of exclusivity. The price jumped from 10 cents per tablet to nearly $5. No patent. Just exclusivity.

Another example: Trintellix, an antidepressant. Its patents expired in 2021. But the FDA had granted 3 years of exclusivity based on new clinical studies. Teva, a generic maker, was ready to launch-but couldn’t. They lost an estimated $320 million in potential sales. Patents were gone. Exclusivity wasn’t.

This is why some experts call market exclusivity a “de facto patent.” It doesn’t require novelty. It doesn’t require invention. It just requires data. And that’s why biotech companies-especially small ones-often rely on exclusivity more than patents. A 2022 survey by BIO found that 73% of small biotech firms use exclusivity as their primary protection tool, especially for reformulated drugs or follow-on biologics.

Why This Matters for Drug Prices

Think about this: the average cost to develop a new drug is $2.3 billion. Most of that goes into clinical trials. That’s why companies need protection. They’re not trying to be greedy-they’re trying to survive. But the system has loopholes.

One of the biggest is the 180-day exclusivity for the first generic company that challenges a patent. If they win, they get a head start on the market. That window is worth $100 million to $500 million in extra revenue. So some companies file patent challenges not to help generics-they do it to block others from entering. It’s a race, and the prize is monopoly profits.

And then there’s the “patent thicket.” A drug might have 20 patents listed in the Orange Book. Even if the main one expires, the rest keep generics out. That’s why 58% of new drugs approved in 2022 had no composition-of-matter patent-but still had regulatory exclusivity. The system is shifting. Patents are weakening. Exclusivity is growing.

By 2027, McKinsey predicts regulatory exclusivity will account for 52% of total market protection time for new drugs-up from 41% in 2020. That’s not a coincidence. It’s policy. It’s law. It’s how the system was designed.

What’s Changing Now?

The FDA launched its Exclusivity Dashboard in September 2023. For the first time, anyone can see exactly when each drug’s exclusivity ends. It’s transparency. But it’s also a target list for generic manufacturers. They’re now racing to file applications the moment exclusivity expires.

And Congress is watching. The PREVAIL Act of 2023 proposes cutting biologics exclusivity from 12 years to 10. Meanwhile, the FDA is requiring more detailed justifications for exclusivity claims starting January 1, 2024. Companies can’t just say “we did studies”-they have to prove exactly what data they submitted and why it qualifies.

But here’s the reality: 22% of innovator companies between 2018 and 2022 failed to claim all available exclusivity periods. That’s 1.3 years of lost protection per drug. That’s money left on the table. And it’s not because they’re lazy-it’s because the rules are confusing. One senior regulatory affairs manager told the DIA Forum that navigating this system costs medium-sized companies $2.5 million a year just in legal and compliance time.

What This Means for You

If you’re a patient: you’re paying for the delay. A drug might be technically “off-patent,” but still be priced like a brand because exclusivity is still active. The FDA doesn’t tell you that. The pharmacy doesn’t tell you that. But it’s why your prescription cost jumped last year-even though the drug’s been around for a decade.

If you’re in the industry: you need to understand the difference. Patents are for inventors. Exclusivity is for regulators. You can’t rely on one to protect the other. A biotech startup might think, “We have a patent, so we’re safe.” But if they don’t submit the right paperwork to the FDA, they lose 5 years of protection. That’s not a mistake-it’s a business risk.

And if you’re wondering why generics haven’t come to market? The answer isn’t always patents. Sometimes, it’s just paperwork. And the FDA is the gatekeeper.

Can a drug have market exclusivity without a patent?

Yes. The FDA can grant market exclusivity based on new clinical data, even if the drug’s active ingredient has been around for decades. The colchicine case is a prime example: no patent, but 10 years of exclusivity after the FDA approved a new formulation. This is why some drugs stay expensive long after their patents expire.

How long does FDA market exclusivity last?

It varies by drug type. New Chemical Entities get 5 years. Orphan drugs get 7 years. Pediatric extensions add 6 months. Biologics get 12 years. The first generic to challenge a patent gets 180 days. These periods can overlap with patents or run independently.

Do patents and exclusivity always expire at the same time?

No. Patents expire based on filing date (usually 20 years), while exclusivity starts at FDA approval. A drug might have 3 years of exclusivity left after its patent expires. That’s why some drugs remain protected even when generics are legally allowed to enter.

Why do generic companies challenge patents?

Because the first generic to successfully challenge a patent gets 180 days of exclusive market rights. During that time, no other generic can enter. That window can be worth hundreds of millions in revenue, making it worth the $8 million+ legal cost per challenge.

Is market exclusivity the same in other countries?

No. The U.S. gives 5 years of data exclusivity for new drugs. The European Union gives 8 years of data protection, plus 2 years of market exclusivity, plus 1 extra year for new uses-totaling 11 years. Rules vary widely, which is why global drug pricing differs so much.

Next Steps: What to Watch For

If you’re tracking drug prices, start checking the FDA’s Exclusivity Dashboard. It’s public. It’s updated monthly. And it tells you exactly when the next wave of generics might hit the market. Companies are already using it to time their launches.

Also watch for the PREVAIL Act. If it passes, biologics exclusivity could drop from 12 to 10 years. That could mean cheaper insulin, cancer drugs, and autoimmune treatments within 2-3 years.

And if you’re in pharma-whether you’re a startup or a big company-don’t assume your patent is enough. Talk to your regulatory team. Make sure you’ve claimed every exclusivity period you’re entitled to. One missed form can cost you millions.

Patents protect inventions. Market exclusivity protects data. One is legal. The other is bureaucratic. Together, they shape the price of your medicine. And neither one is going away anytime soon.

15 Comments