Only two countries in the world-the U.S. and New Zealand-allow drug companies to advertise prescription medications directly to consumers. In 2020, these companies spent over $6.58 billion on such ads-more than 10 times what they spent in 1996. This massive investment in DTC advertising isn't just about selling drugs; it's actively reshaping how patients and doctors view generic medications.

Direct-to-consumer (DTC) prescription drug advertisingis the practice of pharmaceutical companies promoting prescription drugs directly to patients through television, print, and digital media. Unlike most other countries, the U.S. and New Zealand permit this form of advertising, creating a unique environment where drug marketing heavily influences patient decisions.

The Unique U.S. Advertising Landscape

The U.S. and New Zealand stand alone globally in allowing direct-to-consumer prescription drug ads. This started in 1997 when the FDA first permitted broadcast advertising with specific requirements. Since then, spending has exploded. In 1996, pharmaceutical companies spent about $550 million on these ads. By 2020, that number jumped to $6.58 billion. This growth happened while most other countries banned such ads entirely, fearing they mislead patients. The result? A system where drug companies can target everyday people with ads for medications that require a doctor's prescription.

How Ads Drive Prescription Numbers

Research from Wharton's Alpert shows a clear link between advertising and prescription rates. A 10% increase in ad exposure leads to approximately 5% more prescriptions. Surprisingly, 70% of this increase comes from new treatments started because of ads, while only 30% comes from existing patients taking their meds more consistently. This means ads primarily bring in new users rather than improving adherence for those already on treatment.

There's also a "spillover effect" where ads for a branded drug like Lipitor increase use of generic versions in the same drug class. Patients see an ad for a specific brand, ask their doctor for it, and often receive a generic alternative. However, this spillover doesn't mean patients prefer generics-they just get them because the branded version isn't available or affordable. The bigger issue is that patients who start treatment because of ads tend to have lower adherence rates overall.

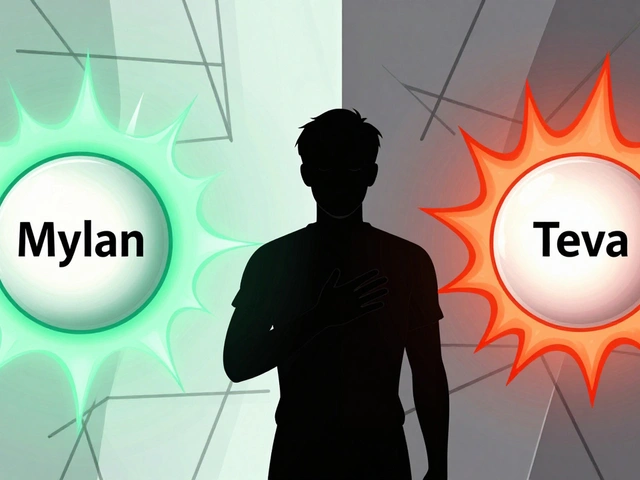

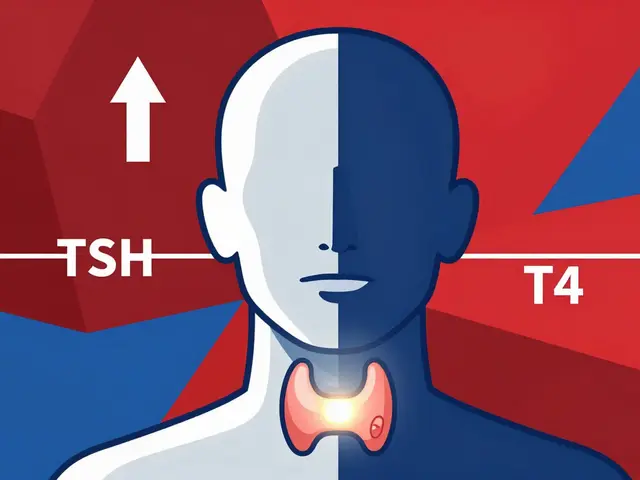

The Branded vs. Generic Perception Gap

When patients see an ad for a branded drug, they often request that exact medication from their doctor. But doctors may prescribe a cheaper generic version. However, research from the University of Montana found that physicians filled 69% of patient requests for interventions they considered inappropriate. For example, a patient might request a specific branded antidepressant after seeing an ad, even when a generic alternative would work just as well. Doctors sometimes comply with these requests, leading to unnecessary costs for patients and the healthcare system.

Pharmaceutical companies spend about $6 billion annually on DTC ads, generating over $4 in sales for every dollar invested. This high return on investment drives continued spending on ads that favor branded drugs over generics. Patients often don't realize that generic medications contain the same active ingredients as brand-name drugs and are equally effective. Ads focus on the branded version's benefits, creating a perception that the branded option is superior.

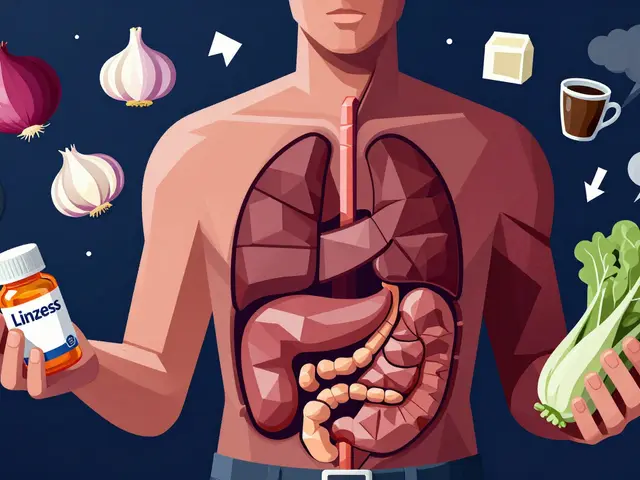

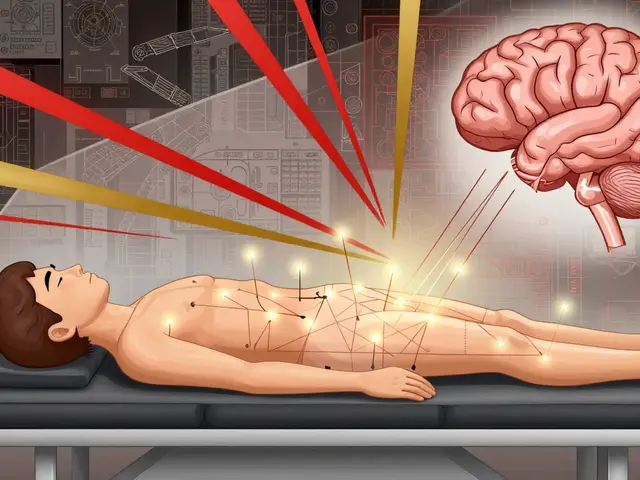

What Ads Don't Tell You

The FDA's 2018 study on ad exposure found that while repeated ads improve recall of some information, risk details are particularly hard to remember. Even after seeing an ad four times, people retained only low levels of both risk and benefit information. This means patients might remember the ad's positive claims but forget the potential side effects or risks. Visual elements in ads-like happy people in scenic locations-distract from critical medical information. A University of Montana analysis of 230 pharmaceutical ads showed that emotional scenes and outdoor imagery often overshadowed drug-specific details, making it harder for viewers to process important facts about generics.

The Real Cost of Misinformation

When patients choose branded drugs over generics due to advertising, healthcare costs rise significantly. For example, a common blood pressure medication might cost $10 per month as a generic versus $100 as a brand. If a patient requests the brand after seeing an ad, they pay more out-of-pocket, and insurers cover the higher cost. This adds up quickly-billions of dollars annually in unnecessary spending. Studies confirm that DTC advertising disproportionately benefits newer, more expensive branded drugs while generic alternatives receive little to no advertising support. This creates a cycle where patients and doctors overestimate the value of branded drugs and underestimate generics.

What's Changing?

Regulators are now reconsidering how DTC ads affect medication choices. The FDA requires ads to include a balanced presentation of risks and benefits, and only promote approved medical uses. However, critics argue the FDA's current rules don't address the indirect effects on generic perception. With digital advertising growing, new challenges arise-like personalized online ads that target specific health conditions. Researchers are exploring whether balanced ad content that highlights generic alternatives could improve medication decisions without sacrificing patient education. For now, the debate continues: should DTC advertising be more tightly regulated to prevent misleading claims about generics, or does it provide valuable disease awareness?

Why does the U.S. allow DTC drug advertising when most other countries don't?

The U.S. and New Zealand are the only countries that permit direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising. This started in 1997 when the FDA allowed broadcast ads with specific requirements. While other countries restrict such ads to protect consumers from aggressive marketing, the U.S. approach is based on the idea that it empowers patients to discuss treatment options with doctors. However, critics argue this has led to misleading information and higher healthcare costs.

Do drug ads actually increase medication adherence?

Research shows mixed results. While ads increase new prescriptions, they only improve adherence for existing patients by 1-2% for every 10% increase in ad exposure. Patients who start treatment because of ads tend to have lower adherence rates overall. This suggests ads may not effectively help people stick to their medication regimens and could even lead to unnecessary use.

Are generic drugs as effective as brand-name drugs?

Yes. Generic drugs contain the same active ingredients as their brand-name counterparts and must meet the FDA's strict standards for safety, strength, and quality. The only differences are usually in inactive ingredients, packaging, or cost. However, DTC advertising for branded drugs often creates the false impression that branded versions are superior, even when generics are equally effective and much cheaper.

How do drug ads influence doctor-patient decisions?

Patient requests driven by ads heavily influence prescribing. A 2005 JAMA study found that standardized patients who requested specific drugs received them significantly more often than those who didn't. In real-world practice, physicians report filling 69% of DTCA-motivated requests for interventions they considered inappropriate. This shows that ads can override clinical judgment, leading to prescriptions that may not be the best option for the patient.

What role does the FDA play in regulating these ads?

The FDA requires that prescription drug ads include a balanced presentation of risks and benefits, and only promote approved medical uses. However, research shows that even with these rules, patients often forget risk information after multiple exposures. Critics argue the FDA's current regulations don't adequately address how ads shape perceptions of generics versus branded drugs, leading to potential misinformation about medication choices.

13 Comments

Generic drugs are just as effective as brand names. It's all about the active ingredients. Simple as that.

Totally agree with you. 🤔 It's fascinating how ads shape perceptions. Like, why do people think branded is better? Maybe it's just marketing magic. 🌍💊

You're absolutely right. It's interesting how the same active ingredients are treated differently based on branding. Maybe we need more education on this.

OMG yes! The ads are so manipulative. I saw one for Lipitor and thought it was this super special drug but then learend generics are the same. So frustrating how they make us think we need the expensive one. 😭

Pharmaceutical companies engage in deceptive marketing practices that prioritize profit over patient welfare. The current regulatory framework fails to adequately address the misinformation perpetuated by DTC advertising, leading to unnecessary healthcare expenditures. This requires immediate legislative intervention.

Whoa there, buddy. You're oversimplifying. DTC ads actually help patients know about treatments they might not have heard of. It's not all bad. Some people need that info to even talk to their doctors. 🤷♂️

Brands over generics no way

Hey, you're totally right about the info part. But let's be real, most of the time ads just push expensive drugs. I mean, if it's the same as generics, why not save money? 🤔 Maybe the system is broken. Typos here, sorry.

I don't know, it's just... I feel like people are too easily influenced by ads. They should know better. It's not hard to look up generics.

It is imperative to recognize that patient education is key in this discourse. The disparity in perception between branded and generic medications stems from systemic marketing strategies rather than clinical efficacy. We must advocate for transparent information dissemination.

Absolutely! Let's get the word out about generics. They're just as good and save us so much money. 💪 Let's push for more awareness!

Mark, I really appreciate your enthusiasm for spreading awareness about generic medications. It's crucial to understand that the active ingredients in generics are identical to their brand-name counterparts, ensuring the same therapeutic effects. However, the perception gap created by DTC advertising is significant. Patients often equate higher cost with better quality, which isn't necessarily true. This misunderstanding can lead to unnecessary financial burdens on both individuals and the healthcare system. It's important for healthcare providers to actively discuss these points with patients, emphasizing the equivalence and cost-effectiveness of generics. Additionally, regulatory bodies should consider stricter guidelines on how advertisements frame the benefits of branded drugs versus generics. By addressing these issues, we can foster a more informed patient population and reduce healthcare costs. Let's keep the conversation going and push for systemic changes that prioritize patient welfare over corporate profits. Many studies have shown that patients who are educated about generics are more likely to choose them, which not only saves money but also helps in maintaining the sustainability of healthcare systems. The pharmaceutical industry's focus on branded drugs through advertising creates a cycle where patients and doctors alike are led to believe that the expensive option is superior, despite the evidence to the contrary. It's time for a shift in how we communicate about medication choices, focusing on facts rather than marketing. We need more public health campaigns that highlight the benefits of generics without the hype. This would help in reducing the stigma associated with generic drugs and ensure that patients receive the best care without unnecessary costs. Ultimately, the goal should be a healthcare system that prioritizes patient health and affordability over corporate profits.

Generics are the real deal. Save money, get same results. Why overpay? 🤷♂️